Lent, leading up to Easter, is a period of abstinence and repentance.

Forty days, where the basic rule is that if it’s fun, it’s probably not allowed.

Carnival originated, at least in part, as a reaction to the meagre forty days, when meat, wine, cakes, and rich foods in general were off the menu.

Hence, we have the fat week leading up to Ash Wednesday, which is the first day of Lent.

Shrove Tuesday is the last day of the carnival — Mardi Gras for the French inclined, martedi grasso in Italy, both meaning Fat Tuesday — but the preceding Thursday was also an important feast.

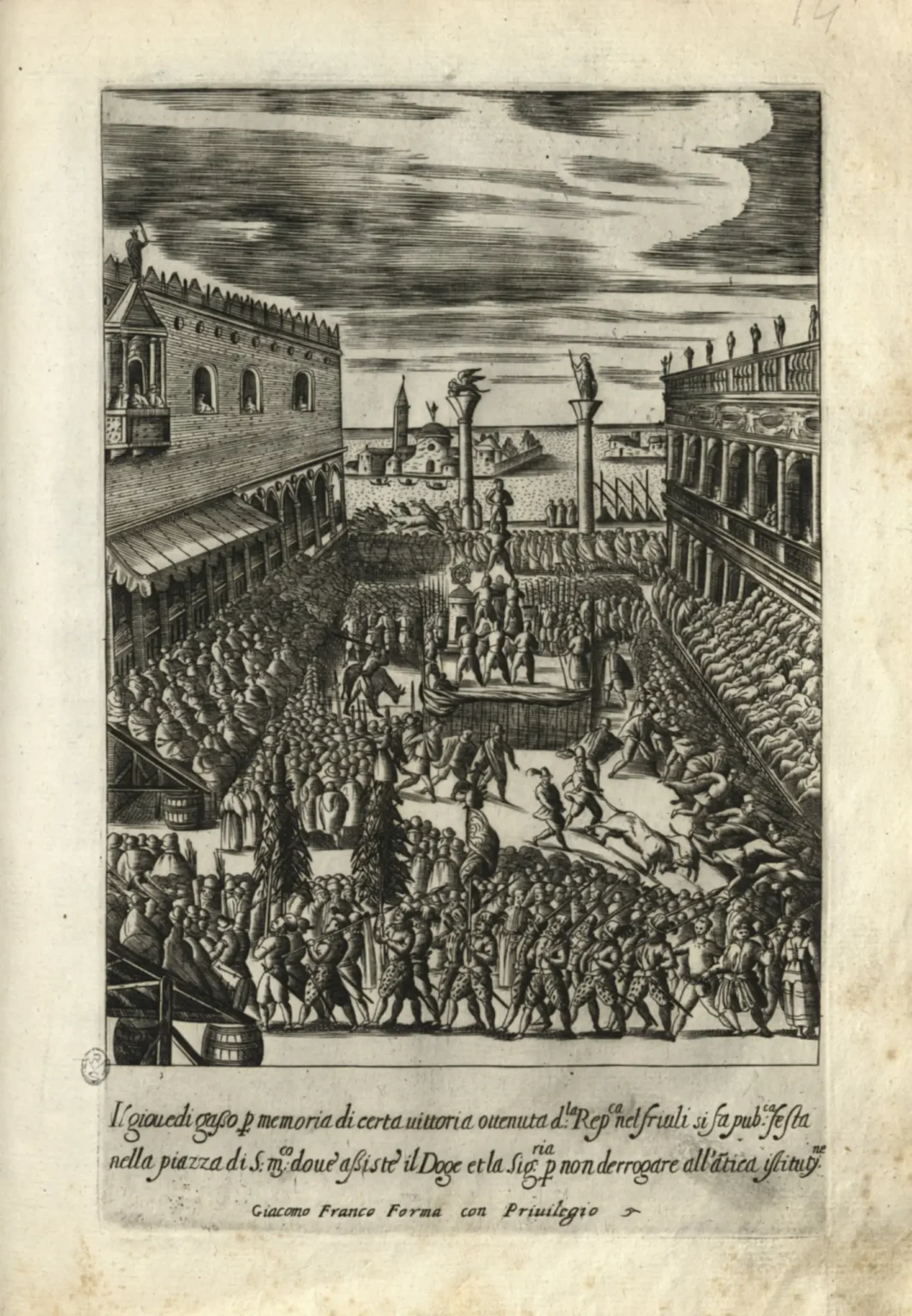

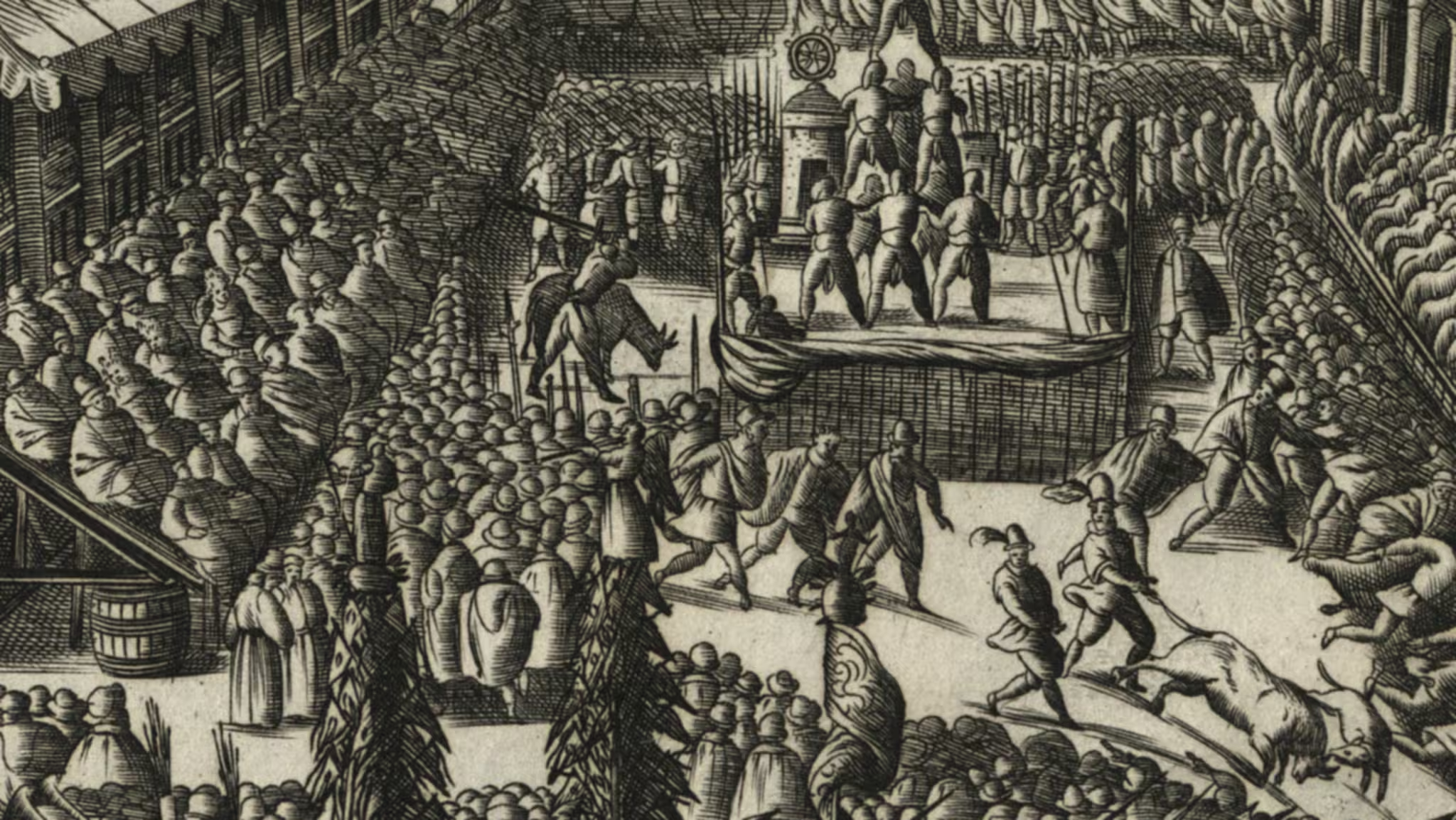

In Venice, this was the Feast of Giovedì Grasso, which was celebrated in grand style in the Piazzetta, the smaller part of Piazza San Marco near the two columns.

For the event, tribunes were erected on both sides with seating for the senators and other magistrates, while the Doge and the Signoria watched from balconies on the first floor of the Doge’s Palace — the Loggia Foscari.

In the Piazzetta proper, a platform for entertainment was constructed, and one or more wooden towers, from which fireworks were lit. All sorts of entertainment occupied the square.

The Castellani and the Nicolotti competed for who could make the tallest human tower, and bulls.

Bull fights were a popular part of feasts and celebrations, both public and private, and there were bulls for Giovedì Grasso, too,

It is all on this print by Giacomo Franco from around 1610:

The text on the print says (my translation): “On Fat Thursday, remembering a certain victory obtained by the Republic in Friuli, there’s a public feast in the square of St Mark, where the Doge and the Signoria participate as to not divert from the ancient institution.”

So, this celebration, during carnival, was not religious at all. It was to remember a victorious war. It was a celebration of the Republic of Venice.

Patriarch on Patriarch

In 1161, Northern Italy was a war ravaged mess.

The wars between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines — the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa — raged, with the Northern Italian communes divided between the two sides.

During this conflict, Barbarossa instigated several attacks on Venetian interests, from Ferrara and Padua.

As Venice was occupied fending them off, the newly appointed Prince Patriarch of Aquileia — the Austrian aristocrat Ulrich II of Treffen — launched a surprise attack on the Venetian Patriarch of Grado.

Ulrich, as a true man of God, personally led his troops on the attack, and quickly took Grado.

The Patriarch of Grado, Enrico Dandolo, fled to Venice.

The main treasure of the Cathedral of Grado were the relics of the saints Hermagoras and Fortunatus. They were, according to legend, two early Christians of Aquileia, converted by St Mark himself, and their remains had been moved to Grado in the 600s during the Lombard incursions. Hermagoras was, again according to legend, the first bishop of Aquileia, invested by St Peter himself.

Patriarch Ulrich moved the relics back to Aquileia.

Venice, however, reacted more swiftly than Ulrich had anticipated. The doge, Vitale II Michel, organised a fleet, sailed to Grado, and in a surprise attack retook the city.

Not only did the Venetians retake Grado, they also captured Ulrich, twelve canons, and many of his vassals.

Moving quickly, Venetian troops surged forward, and destroyed as many of the castles of the counts and barons of the Patriarch of Aquileia as they could.

They also recovered the relics of the Aquileian proto-saints.

This very short battle took place of Fat Thursday of 1162.

Patriarch Ulrich and his twelve canons were taken to Venice, paraded around the city, and only released later, on the condition that the Patriarchy of Aquileia, annually, in perpetuity, for Fat Thursday, would send twelve fat pigs and twelve loaves of bread to Venice.

Pigs and bulls

These pigs and loaves became the start of the feast of Giovedì Grasso in the Republic of Venice.

Initially, the pigs were let free in the squares and alleyways, so people could chase them for food, but later they were slaughtered, and the meat distributed to the sixty members of the Venetian Senate.

While the poor were chasing pigs, the doge and the Signoria met in the Sala del Piovego — one of the main courtrooms in the Palazzo Ducale — where they smashed wooden models of castles with large clubs, in a kind of re-enactment of the victory over the Patriarch of Aquileia and his vassals.

This was discontinued in the early 1500s by doge Andrea Gritti, who had some very real military experience from the Wars of the League of Cambrai, and found the spectacle ridiculous.

After the Venetian conquest of the Prince-Patriarchy of Aquileia in the mid-1400s, they had little need to require the annual tribute, and the funds for the feast were found in Venice.

Many other games and spectacles took over from the pig chase, several of which are depicted on the print above.

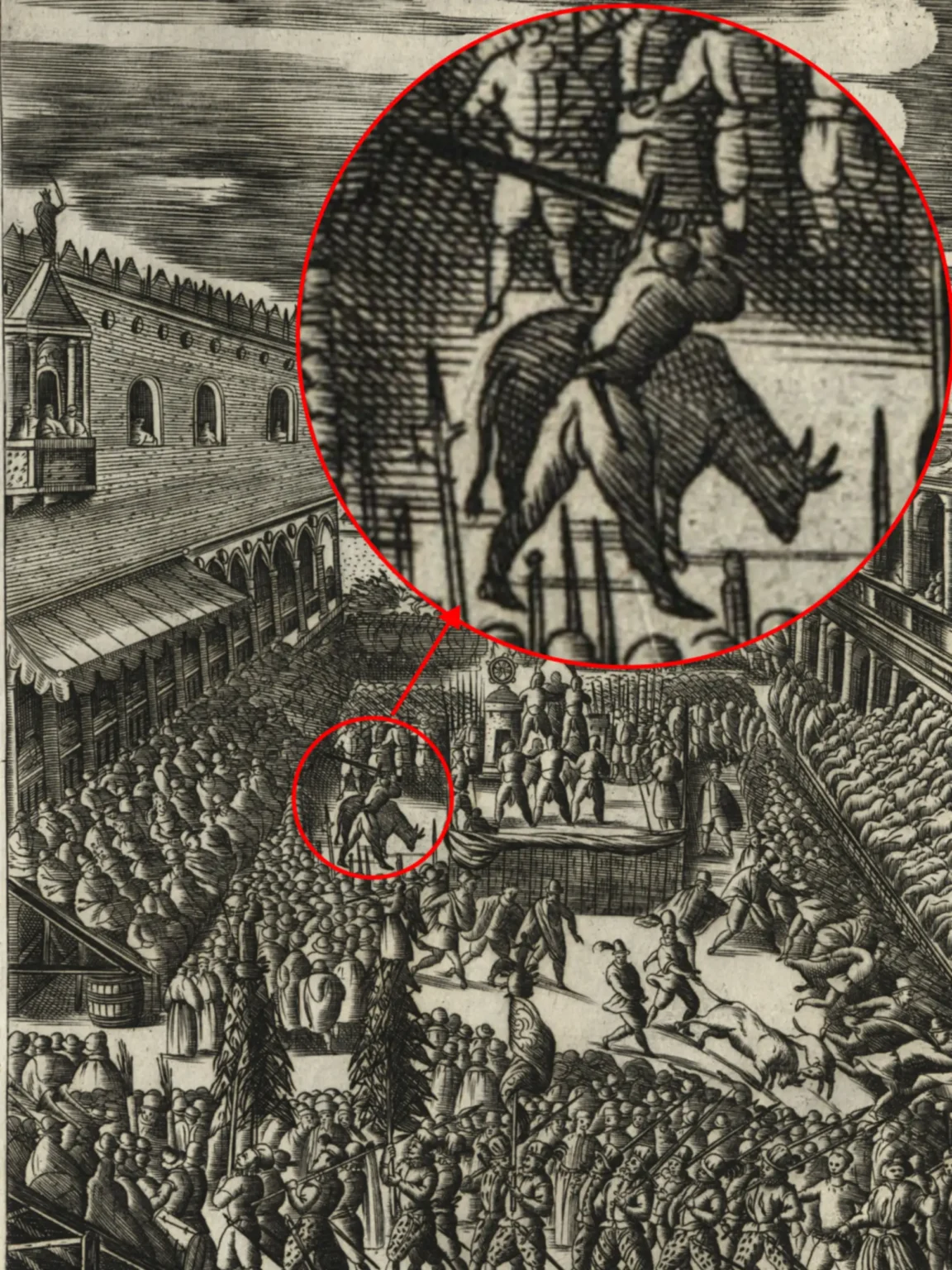

While the earliest sources all concur on a tribute of twelve pigs and twelve loaves, somehow the story changed into one bull and twelve pigs. It is not clear when and why the bull entered the story, but the public slaughter of a bull was soon an important part of the feast.

It appears that the bull and the twelve pigs became a representation of the defeated Patriarch and his twelve canons.

Consequently, the slaughter of the bull developed into a symbolic execution: decapitation by sword, as was suitable for somebody of noble birth.

If we zoom in on the print above, the beheading of the bull is there, quite centrally in the scene.

Another work of art, by Alessandro Piazza, from the very late 1600s or early 1700s, shows the same celebration, from the opposite side. Here too, the execution of the bull is clearly depicted.

The executioner was a representative of the guild of the blacksmiths or of the guild of the butchers. In either case, he was chosen among the physically strongest, as the head of the bull had to come off with one clean blow of the large two-handed sword.

There’s a portrait of such a blacksmith, all dressed up for the celebration, carrying the blunted sword as in procession, in the Gli abiti de veneziani by Giovanni Grevembroch.

In the modern carnival, on Shrove Tuesday, at the very end of the festivities, they burn a large straw figure of a bull.

I don’t know exactly why they do it, but it might have a line back to this symbolic bull sacrifice at the time of the Republic of Venice.

Somehow, I doubt the public beheading of a live bull by two-handed sword in the Piazzetta would be legal today.

In an earlier newsletter, I wrote about a somewhat similar story about a medieval war, and a symbolic tribute of live animals: the War of the Castle of Love, which I have also covered on the Venetian Stories podcast, in episode 14.

Leave a Reply