When the English gentleman John Evelyn left Venice in 1646, after almost a year in Venice and Padua, he had more stuff than when he had arrived.

From his diary for late March 1646:

Having packed up my purchases of books, pictures, casts, treacle, &c., (the making and extraordinary ceremony whereof I had been curious to observe, for it is extremely pompous and worth seeing) I departed from Venice …

Unsurprisingly, Evelyn had been shopping books and works of art, but also treacle made with extremely pompous ceremony.

The treacle was Venice treacle, one of the main export articles of the Republic of Venice.

Venice treacle was the English name for Theriac (or teriaca or triaca), which was considered a kind of wonder medicine. In fact, the word ‘treacle’ is derived from ‘theriaca’.

A sales brochure for Venice treacle — probably from the late 1600s, printed in Venice, in English, by a Venetian pharmacy — stated (among many other similar claims):

It cures the Plague itself, and all pestilential deseases, and is a singolar preservative against the same.

It is god for the bitings of all venomeous animals, and especially for those of scorpions and mad Dogs, and of ail other animals vvhatsoever, vvhether of Land or of Sea, taking it invvardly, and also applying it outvvardly upon the said bitings.

It dissipates all Windiness of the stomach, is excellent against pains in the bovvels and the reins, caus’d by ulcers or the stone.

It kills all sorts of vvorms, driving them out of the body, and prevents their breeding.

It drives out the afterburden vvhen retain’d as likevvise dead creatures from Women’s body’s.

It has many other virtues, vvhich for brevety’s sake are omitted, it being a classic remedy, and knovvn to all the World.

As should be evident, the Venetian printer had some issues with the letter ‘w’.

The last point was not an exaggeration. Theriac was ancient, and it was known across much of the world.

The earliest start was in the Kingdom of Pontus in the first century BCE. King Mithradates IV was fearful of being poisoned by his enemies, and had his physician combine all the known antidotes into one super-antidote, called mithridatium.

When Pompey the Great defeated Mithridates and heard about the miracle antidote, he had all the spoils of war searched, until the recipe was found. From there, it spread among the doctors in Rome.

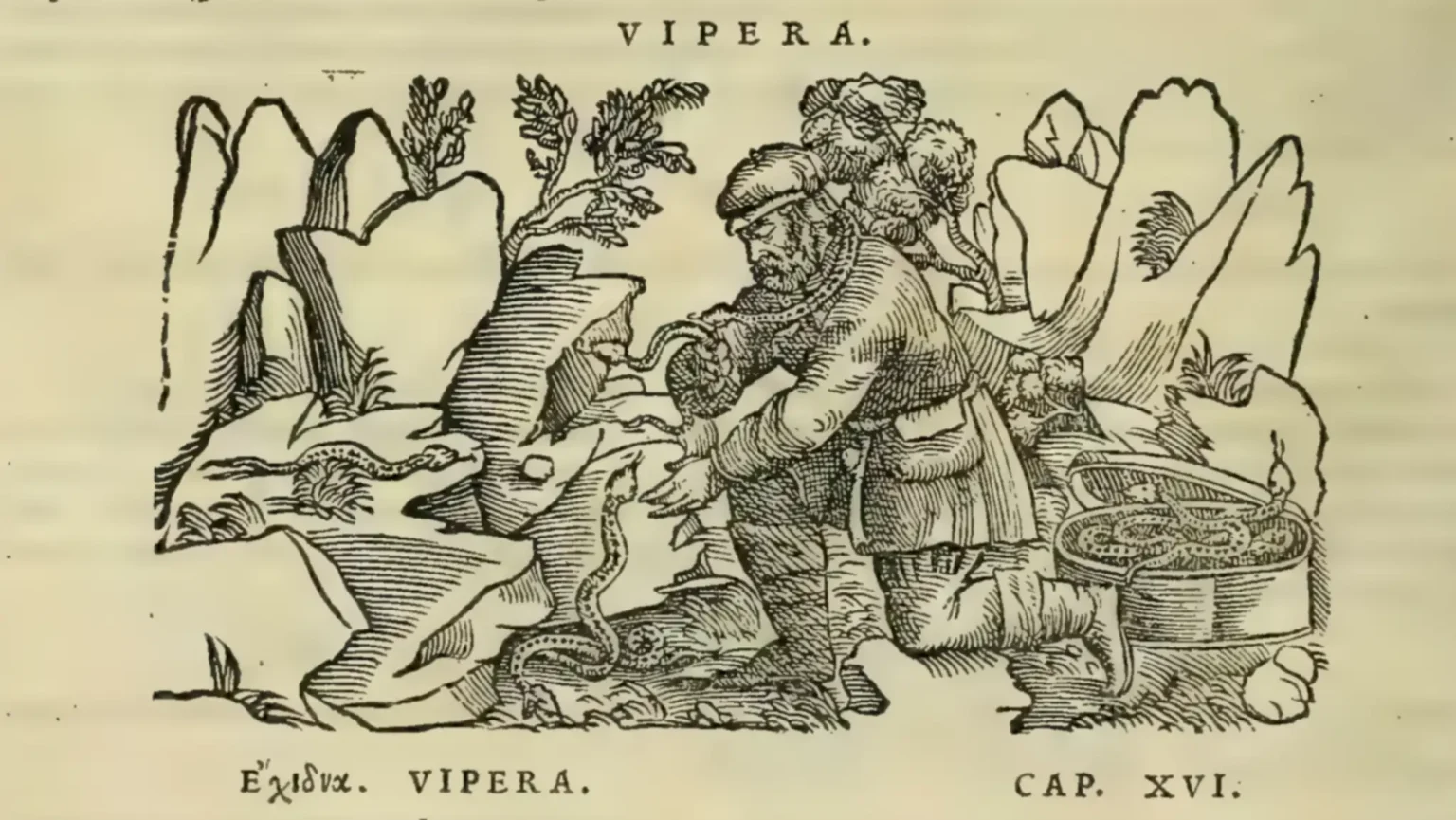

Andromachus the Elder, physician to Nero, elaborated on mithridatium, adding many new ingredients, most notably the flesh of vipers, and thus invented theriaca. A century later, Galen of Pergamon wrote a treatise on the marvellous effects of theriac, which survived in Byzantine and later in Arab libraries.

Venice, which was born Byzantine, developed a trade network in the Levant, which brought it both knowledge and goods. Venice therefore learned to make theriac before most other European nations, and also had access to the ingredients.

Theriac requires over sixty different ingredients, the vast majority vegetable, but also animal and mineral. While many of the ingredients were from around the Mediterranean basin, some came from distant places: nutmeg from Indonesia, opium from Egypt, plants from India, castoreum from Pontus (scent glands from beavers), bitumen from the Dead Sea, and much more.

Only an empire could concoct such a medicine. Just acquiring the ingredients required a trade network, which spanned most of the known world. It also required money. Lots of money.

The Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire and the Caliphate had those resources, and so did Venice in the late Middle Ages.

The recipe used by the pharmacists in Venice was kept secret, and Venice therefore acquire a virtual monopoly on supplying Theriac to most of Western Europe.

A French pharmacist got hold of the recipe, and published it in France in 1669. Venice had to work harder to keep its market position, and regulated the production of Theriac in Venice, basically to protect the brand.

Pharmacists had to be licensed to make Theriac. They had to display the ingredients in public in front of the shop, for three days, before making a batch. Finally, the actual work of grinding all the ingredients to a fine powder, and mixing all the resins, gums and liquids, also had to happen in public, overseen by representatives of the College of Physicians and of the Venetian health authorities.

These requirements, and the complexities of collecting and preparing all the many ingredients, meant that each pharmacy did one or two large batches of theriac a year.

The events became great shows, where the display of the ingredients, the noise of the workers pounding the large bronze mortars, the formally dressed authorities, mixed with the intense smell of the many exotic ingredients.

People came to watch the miracle medicine being made, and the pharmacies put on even more of a show, to promote their wares. The making of Venice treacle became a tourist attraction in its own right.

Seeing one of those shows was clearly on the to-do list of John Evelyn when he arrived in Venice in 1645, and so was bringing back home one of those pewter jars with the symbol of the pharmacy on the lid.

The production and sale of Theriac was big business, for Venice and for many others. Theriac was the undisputed king of remedies well into the 1700s, and it was in common use into the 1800s.

One must imagine that it had some effect on the many ailments it was used for?

Well, no!

Medically, Theriac was little more than a placebo.

The only likely effect would be from the small amounts of opium present, which might relieve some pains and offer some relief from diarrhoea.

Was it an elaborate — and centuries long — fraud, at the expense of gullible consumers?

Also, no!

The apothecaries, who made it, and the physicians, who prescribed it, all believed it to be a wondrous remedy for almost everything.

Before modern medicine, most remedies were traditional, and made from various natural substances, predominantly herbal. Theriac was,

Theriac was, in a way, an expression of the best they could do within the cultural and scientific boundaries of their time.

When those cultural and scientific boundaries started to shift substantially in the 1700s, criticism of traditional remedies like Theriac began to appear, and its use started to decline, to practically disappear in the 1800s.

It was supposedly still available in some pharmacies in Italy until the 1930, but today it would probably be illegal.

Additional reading:

Leave a Reply