Why is the railroad station in Venice called Santa Lucia?

Venice is, of course, much older than the railroad station, and where the station is today, there was something else before. There was quite a bit, actually.

On the area, which is now occupied by the station, the square in front of the station, the railroad tracks behind it, and the office building besides it, were once two churches, two monasteries, an important charity and several large gardens.

The churches were the Chiesa di Corpus Domini and the Chiesa di Santa Lucia, each with an associated nunnery, and between them was the seat of the Scuola dei Nobili.

Thanks to the Venetians’ love of vedute, we have some images of how the area looked, at least in the 1700s.

The largest of these buildings was the Church of Santa Lucia, which stood more or less in the middle of the square in front of the current station.

The monastery of Corpus Domini was exclusively for noblewomen, and the charity of the Scuola dei Nobili only allowed noblemen as members. The two were connected, as the main purpose of the Scuola dei Nobili was to organise the annual procession of Corpus Domini in St Mark’s square.

The Church of Santa Lucia wasn’t always dedicated to her, and, in any case, what has Santa Lucia got to do with Venice?

Who was Santa Lucia

Santa Lucia was Sicilian, from Syracuse, and she lived around the year 300, long before there was a Venice. She was, most likely, Greek speaking, as that part of Sicily had been Greek for a thousand years, and was never really Romanised before it became Byzantine.

She was a Christian, but her father wasn’t. He betrothed her to another non-Christian, and Lucia, unable to bear such a marriage, gouged her own eyes out.

No longer physically complete, the marriage couldn’t happen, but, as was also often the case, Lucia died shortly after.

She was buried in the catacombs under Syracuse, and almost immediately venerated as a saint.

When Muslims conquered Sicily in the 800s, her remains, along with many other Christian treasures, were moved to Constantinople.

Centuries later, with the Fourth Crusade in 1204, her relics were looted by the Venetians, and taken to Venice.

They were placed in the church of San Giorgio Maggiore, just across from St. Mark’s.

Her feast day is on December 13th, which in the ancient Julian calendar was winter solstice, and together with the story of her eyes, she became the patron saint of eyesight, and of the return of light.

During the 1200s, throngs of boats crossed the basin for the island each year on December 13th, until disaster struck. The wind rose suddenly, a many boats capsized, and hundreds of pilgrims either drowned or succumbed to hypothermia.

Consequently, she was moved in 1280. The destination was a church in Cannaregio, which was rededicated in her honour.

She rested in peace there until 1476, looked after by the noble nuns of Corpus Domini.

Theft of a saint

Her church was initially a parish church, but as there were fewer parishioners, the church passed to another group of nuns, the Servites of Mary. These nuns were lower class women.

The noble nuns of Corpus Domini saw this as a gross offence. A saint like Santa Lucia could not fall to simple, common nuns.

Consequently, in the dead of night, they went the few tens of metres to the neighbouring church, took the relics, and brought them back to their own ‘noble’ church.

Now, the Republic of Venice couldn’t have nuns roam around at night stealing relics, noblewomen or not, and the remaining parishioners complained about the theft of their divine protector.

An official herald, dispatched to tell the nuns to return the relics, was turned away at the door.

The Council of Ten then dispatched some armed guards to intimate the nuns to behave, but they were turned away too. The noble nuns didn’t budge, and refused to give up their treasure.

In view of such insubordination, the authorities took more drastic measures.

They sent a bricklayer.

As he started walling up their doors and windows, the nuns realised that the Republic didn’t budge either, and after a while, they surrendered the bones of their beloved saint.

She returned to her church.

This time, her repose lasted until the 1840s, when the Austrians decided that the site of her church, monastery and garden was a good place for a railroad station.

The remains of Santa Lucia went travelling again, this time to the nearby church of San Geremia, where she still is.

The Railroad station of Santa Lucia

Consequently, her church was demolished to make room for the first railroad station of Venice, which stood closer to the Grand Canal, exactly where her church had been.

Her name remained, however, as the name of the station.

Santa Lucia never travelled in her short lifetime, but she’s been out about ever since she died, and now her name is associated with railroad travellers.

Maps and paintings

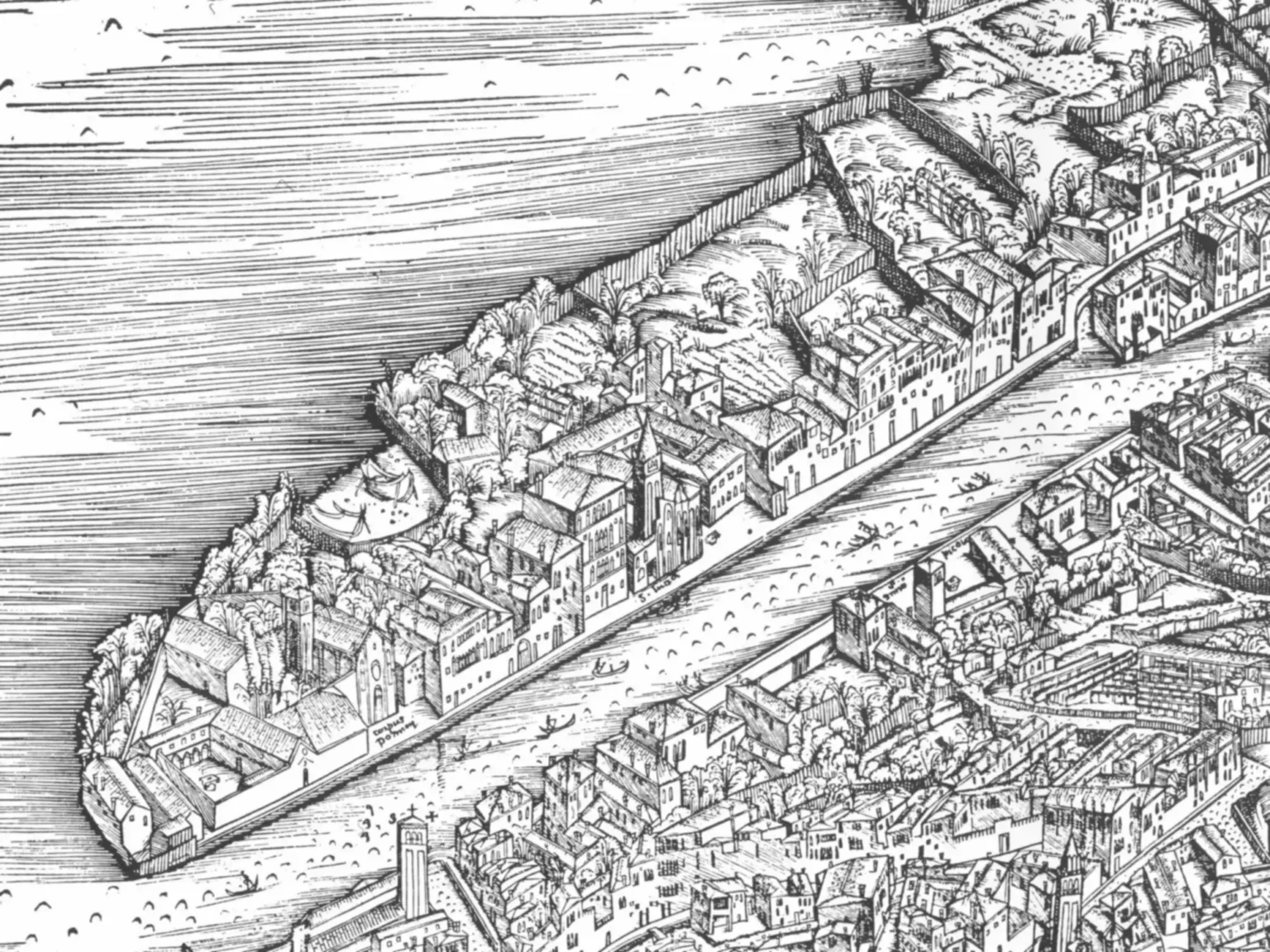

This is the area of the current railroad station appears of the bird’s-eye view of Venice by De Barberi from 1500:

And the same area from the map of Venice by Lodovico Ughi from 1729:

And finally, a view of all three churches in a painting by Bernardo Bellotto:

Leave a Reply