The ancient Venetians enjoyed their well-known sports such as human towers, bull fights and fights on bridges using fists or sticks, not to speak of chickens on a pole, squashing cats bareheaded, and tearing the heads off geese while jumping in a canal.

These were, however, mostly entertainments and games for the lower classes.

Decent people, and nobles, engaged in more exotic activities, such as tennis, football and other ball games.

One such ball game, usually just called giuocar al pallone — playing at ball. It is a game, which probably originates in the Middle Ages.

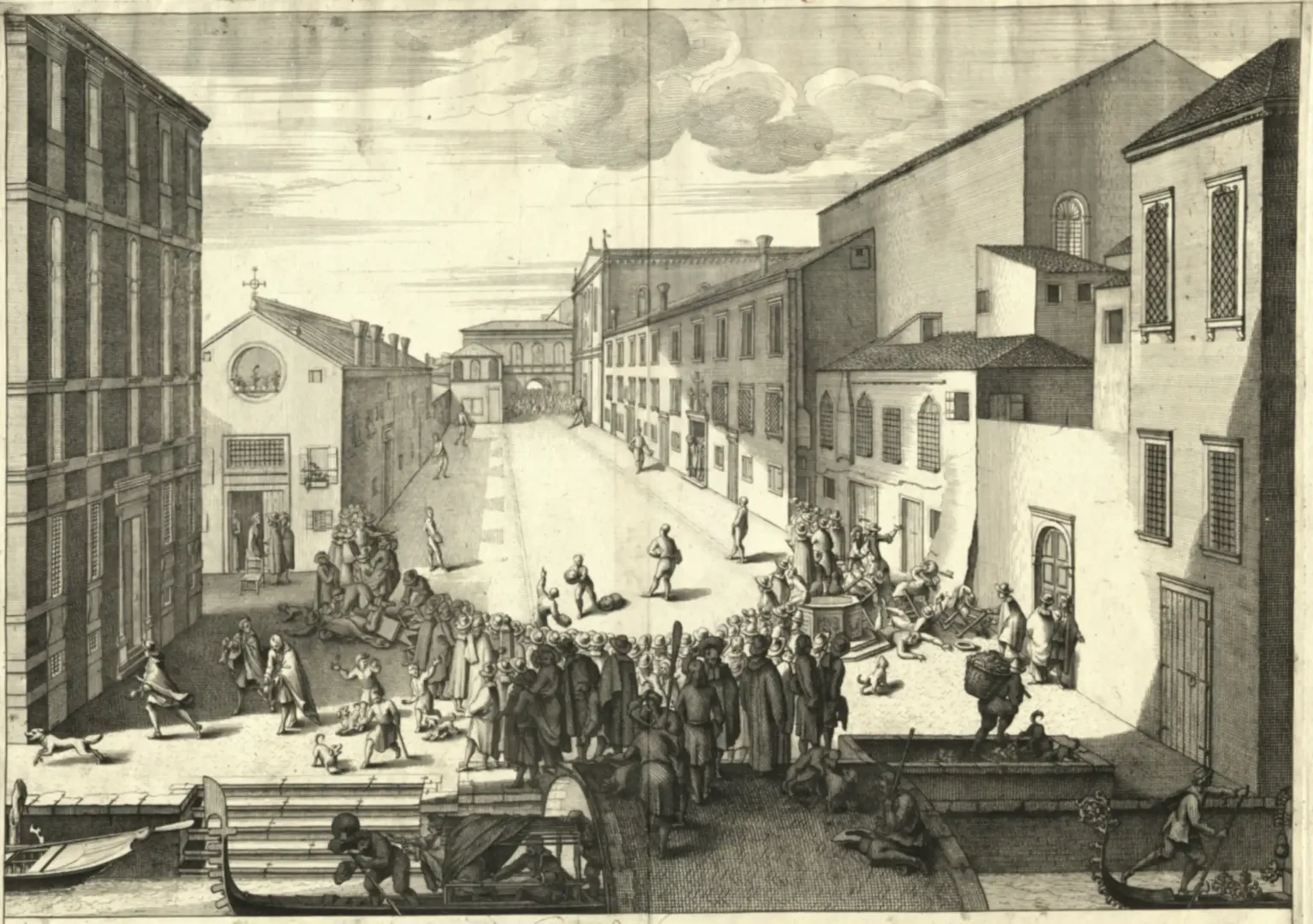

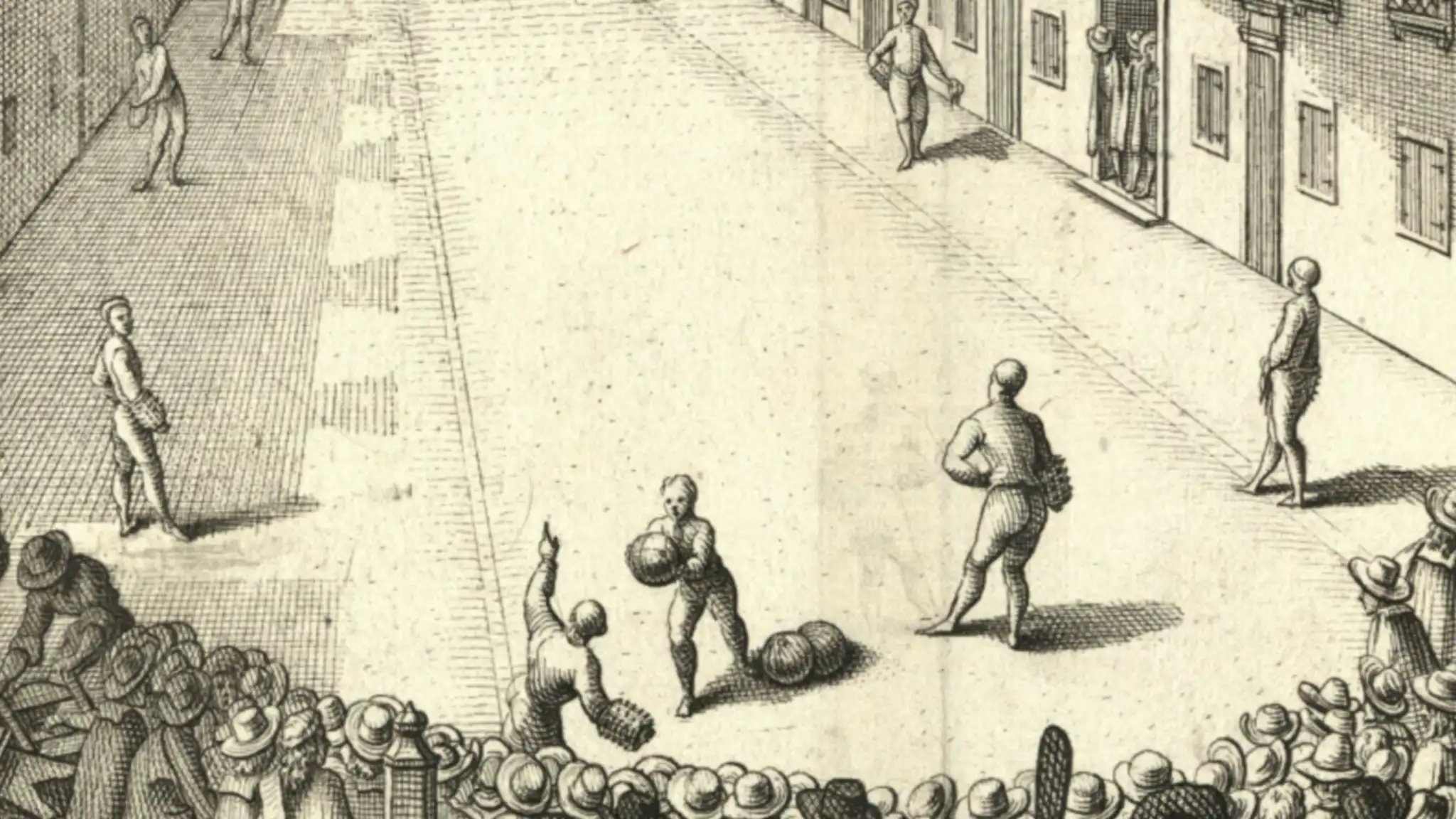

Here’s an image of the game, from c. 1717, by the printer and engraver Domenico Lovisa.

It depicts the Campo dei Gesuiti, which is still there, albeit slightly changed over the centuries.

The game takes place in the open area behind the crowd in the foreground. They are the spectators. There’s another crowd of spectators in the back, in front of the church.

Gameplay

So what was the game?

Like tennis, the game was to hit a ball back and forth over a field, until somebody committed a fault in returning the ball. However, there was no net and no rackets. Also, there were two, three or four players on each side.

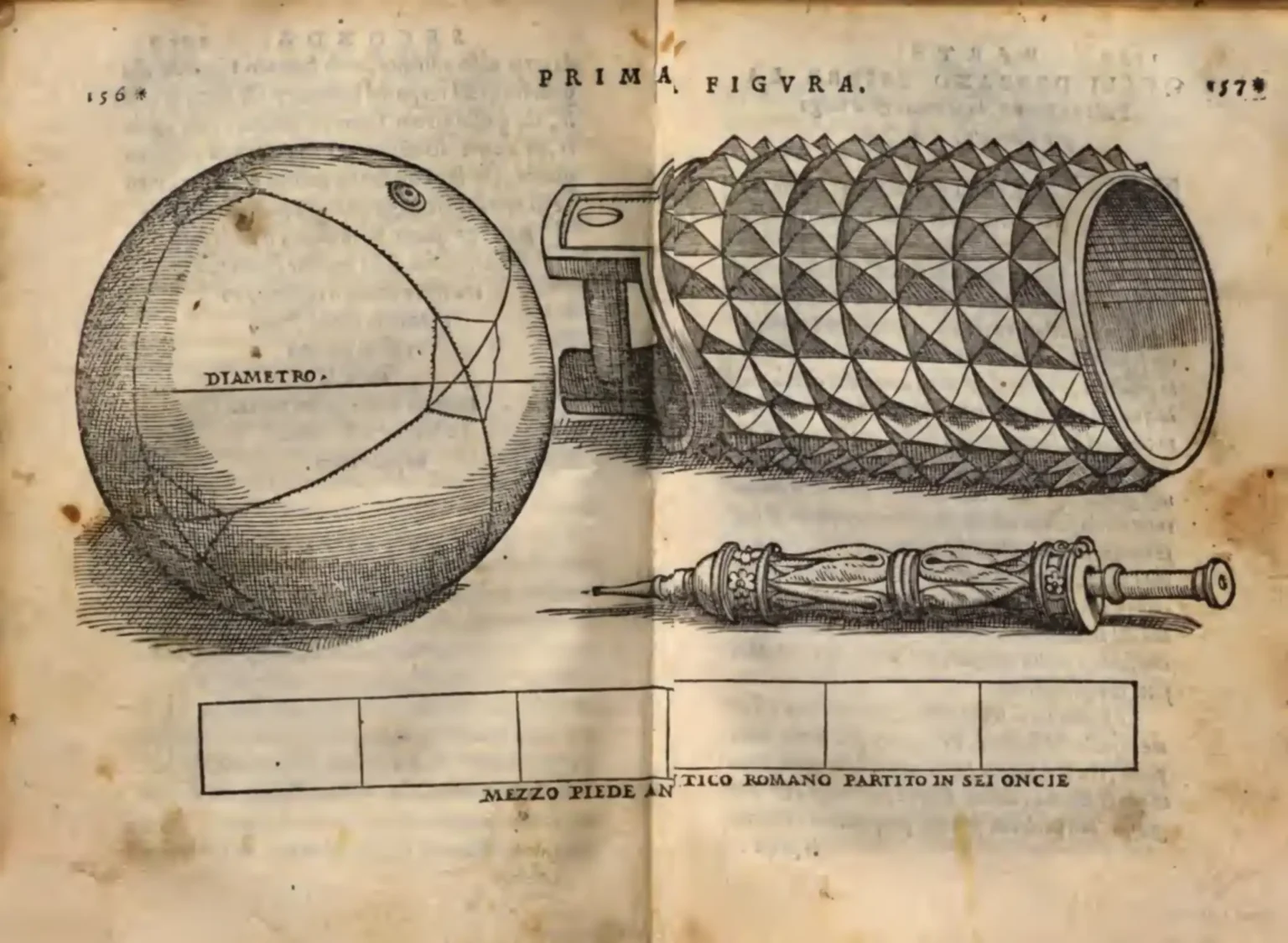

Instead of a racket, the players wore a brazzal — bracciale in Italian — on their right forearm. It was an arm guard made of a piece of wood, normally walnut, hollowed out, with a handle across at the bottom, to grab with the hand. On the outside, the brazzal had protruding teeth, later standardised as seven rows of fifteen spikes. It usually weighed around 2 kg.

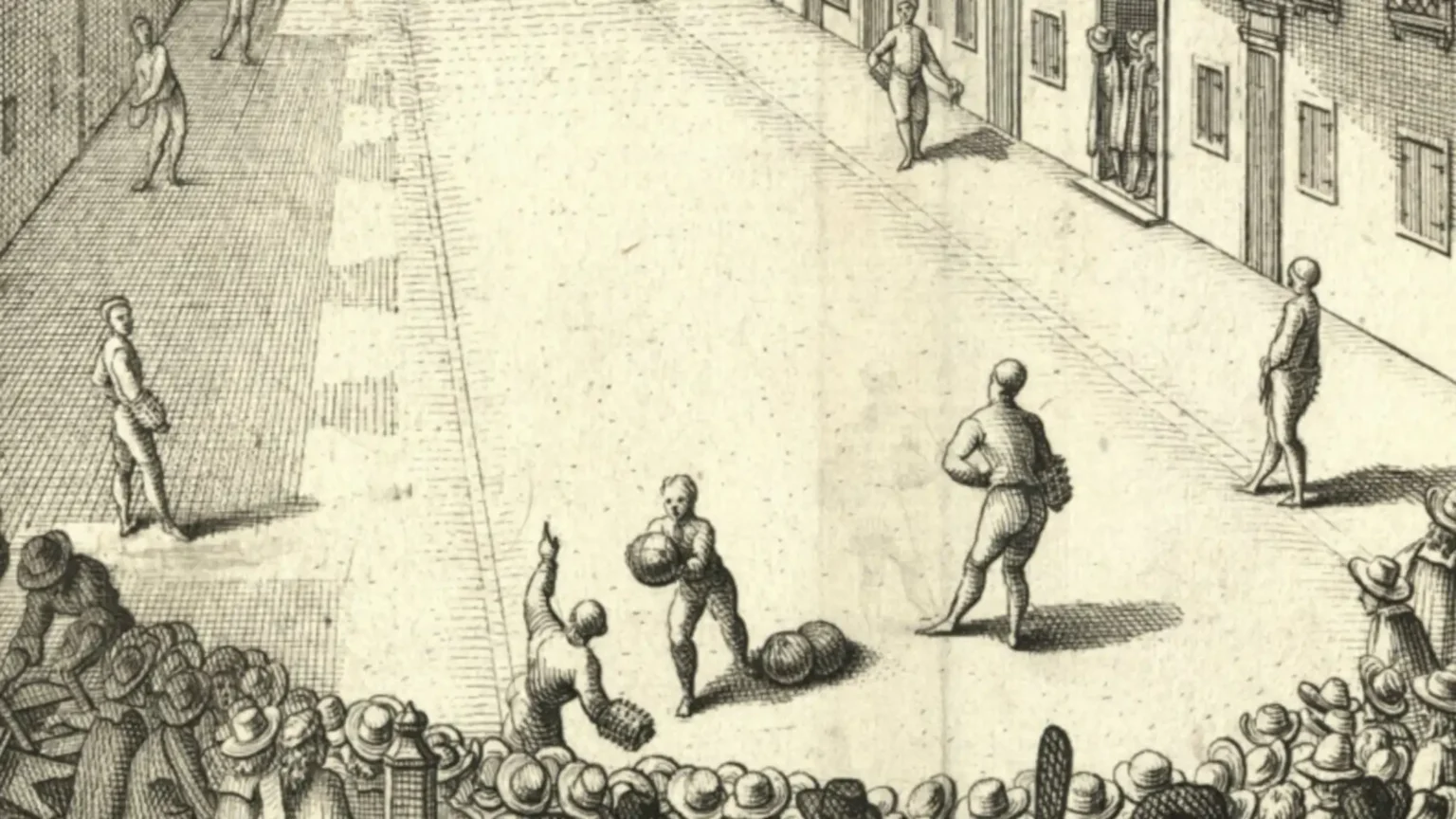

Here’s a zoomed-in detail of some of the players in the above engraving.

Each set started with a helper launching the ball in the air, so the first player could hit it. He was the mandarin — from mandar, to send. In later times, expert players of boccia were given this role, due to their skill in throwing balls with great precision.

The first player would hit the ball in the air with his brazzal, and blast it across the field, for the other side to return.

The ball was allowed to bounce off the ground at most once before being returned. Otherwise, the cazza — Italian caccia, which means ‘game’, as in hunted animals — was lost. Another way to lose a cazza was to send the ball off the end of the field, or way off the sides. It had to be returned within the reach of the other team.

Points were counted 15 for each cazza, and a game finished when one side reached sixty. Later the points became 15–30–40–50, instead of 15–30–45–60.

The serve changed side every second game.

The spikes on the brazzal allowed a skilled player to spin the ball, to make it harder for the opponent to return it correctly.

Sometimes, if the playing field had a suitable wall on one side, it could be allowed to bounce the ball off the wall, but I haven’t heard of such places in Venice.

Equipment

The ball itself was made of leather, inflated, and about the size of a modern football, or a bit larger. The size was standardised and there were specialised makers of palloni in Venice.

We have a treatise on ball games from 1555, by Antonio Scaino, where there’s a neat illustration of the equipment of the game, including measures.

They even had pumps for inflating the balls, and people on hand who were skilled at this.

Accidents

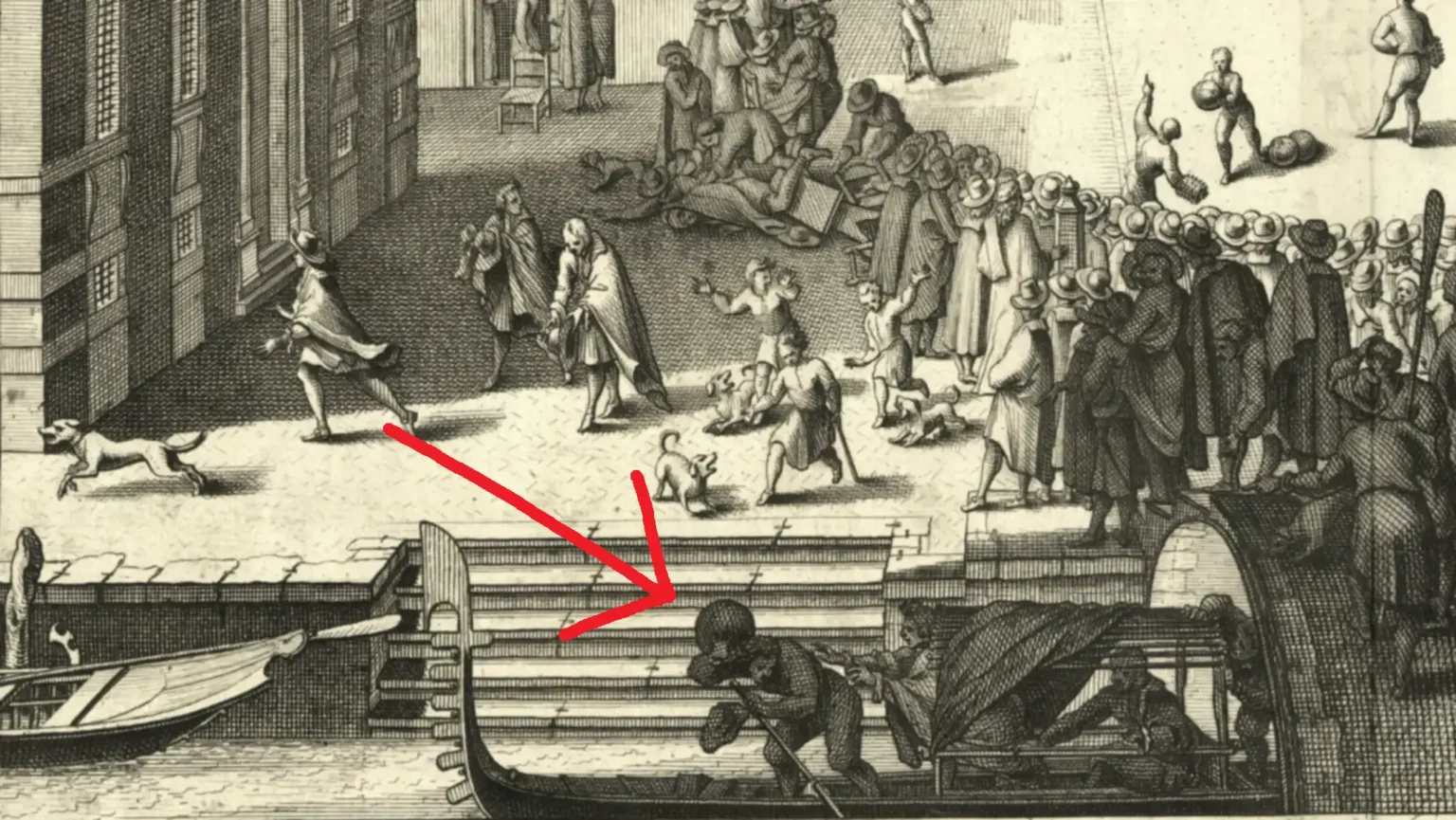

The force imparted on the ball by the blows with the brazzal was substantial, and faults sent balls a bit everywhere, which Lovisa depicts rather humorously in his engraving.

Here’s a detail where the ball has hit some of the spectators:

On the other side, there’s also toppled over spectators, and a few are leaving the place disgusted.

The ball has gone through the crowd, and hit the rower of a gondola in the head, knocked off his hat, and greatly worried his mistress.

Maybe, just maybe, there’s a slight critique of the violence of the game here.

Later times

The lasting popularity of this sport is attested by the many related terms present in the standard dictionary of the Venetian language, by Giuseppe Boerio (1829). All the basic elements of the game, the equipment, the moves and the faults, are present in his dictionary.

The similar terms for the Venetian version of football or rugby are not in the dictionary. Boerio, like Scaino, probably regarded the giuoco al calcio as a less noble sport.

This game was not a unique Venetian sport.

It was played over much of northern and central Italy, and after the unification of Italy in 1860, it was considered a national sport, with tournaments and competitions. Its popularity waned in the early 1900s, when imported sports like modern football and tennis arrived in Italy.

It is still played locally in some parts of Italy, but not in Venice any more.

Bibliography

- Boerio, Giuseppe. Dizionario del dialetto veneziano. Venezia : coi tipi di Andrea Santini e figlio, 1829. 🔗

- Lovisa, Domenico. Il Gran teatro di Venezia ovvero descrizzione esatta di cento delle più insigni prospettive, e di altretante celebri pitture della medesima città, il tutto disegnato, e intagliato eccelentemente da periti artefici, con la narrazione della fondazione delle chiese, monasteri, spedali, isolette, e altri luoghi sì pubblici, come privati. Venezia per Domenico Lovisa sotto i portici a Rialto, 1715. [more] 🔗

- Scaino, Antonio. Trattato del giuoco della palla di messer Antonio Scaino da Salò, diuiso in tre parti. Con due tauole, l'vna de' capitoli, l'altra delle cose piu notabili, che in esso si contengono. In Vinegia appresso Gabriel Giolito de' Ferrari, et fratelli, 1555. 🔗

Leave a Reply