The Venetian carnival was famous, and was so already in the Middle Ages. Kings travelled across Europe to see the Venetian carnival. It was one of the must-see things for travellers to Venice. The carnival was not, however, like the modern cheap replica. The ancient Venetian carnival sported such noble activities as pig-chasing in the alleyways, a flying Turk delivering flowers, and the public execution of a bull by sword.

Links

- Episode 24 — Festa delle Marie

- Clara — the star of the Carnival

- An Englishman in Venice

- An earl, a girl and a gondola

History Walks Venice.

Images

The first six illustrations are from Gli abiti de veneziani (1754) by Giovanni Grevembroch. The print is from Habiti d’huomeni et donne venetiane (1610) by Giacomo Franco, and the painting by Pietro Longhi (1751).

- Mascare — Masks — Grevembroch 3-92

- Nobile al Ridotto — Nobleman at the Ridotto — Grevembroch 1-91

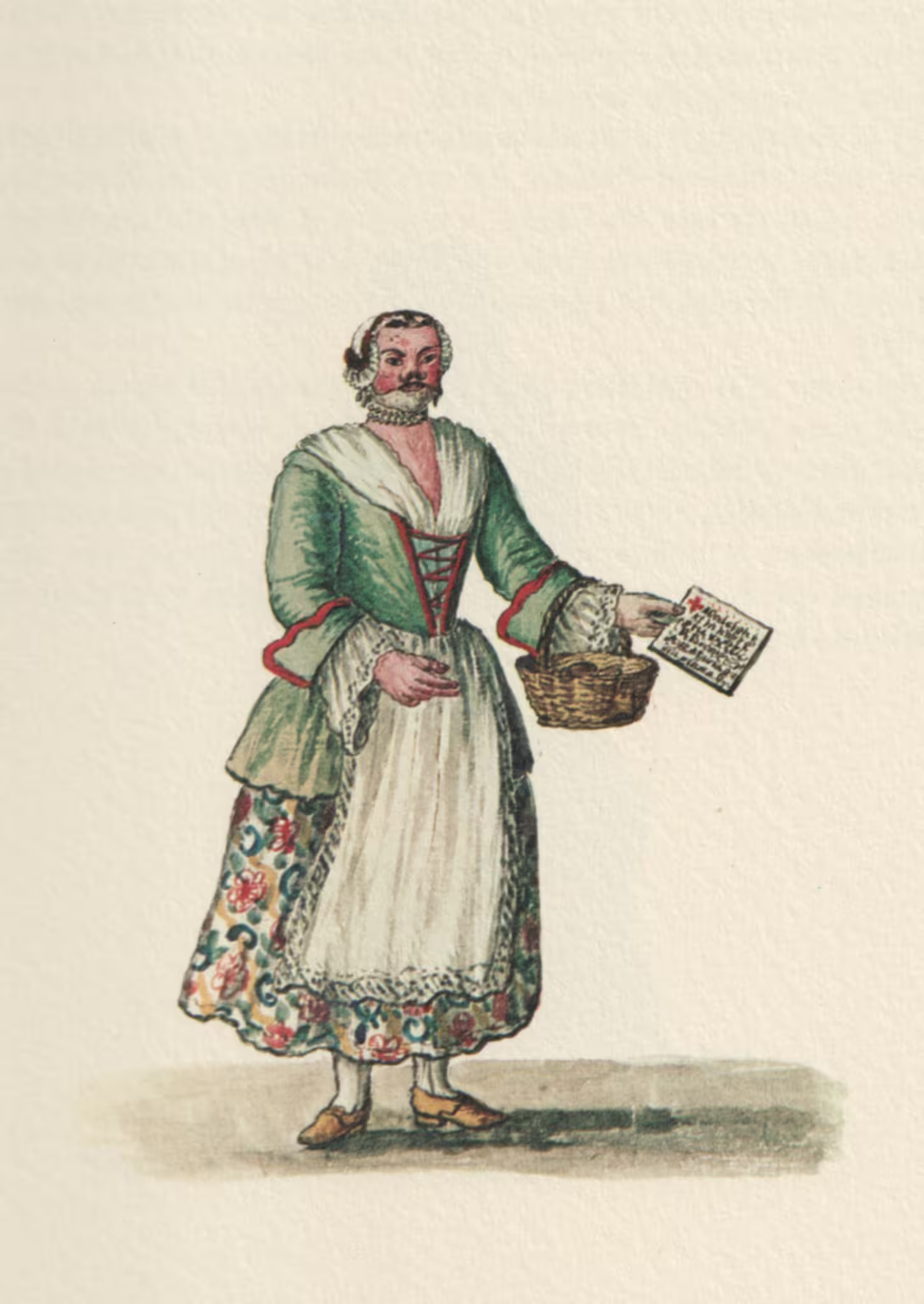

- Gnaga — Grevembroch 3–89

Transcript

Episode 25 — The Venetian Carnival

Carnival is not a Venetian invention, and there are, and have been, many types of carnivals around the world.

The wider European carnival tradition, of which the Venetian carnival was a part, has two very different roots.

There’s a Christian element, which is related to the abstinences required for the forty days of Lent, and there’s a pre-Christian element, from the ancient Roman celebration of the Saturnalia.

Saturnalia

The Roman Saturnalia was an ancient religious celebration, which it took place around the winter solstice, which the Julian calendar placed on December 13th.

During the multi-week festivities, social roles were sometimes overturned, so the masters served the slaves, the women commanded the men.

In a stratified class society, where the rights and obligations of an individual are determined by their class, that status must be clearly signalled. The most obvious way of doing that is through the clothes, so people of different classes had dress codes they had to follow.

Since rights and privileges followed the class, if an individual dressed as somebody of a higher class, they were de facto claiming rights and privileges, which weren’t theirs.

Jumping a bit forward to the Republic of Venice, with a bit of practise, it is fairly easy to see on a painting or a print, which class each figure belonged to. Nobles dressed differently from citizens, who dressed differently from artisans and common labourers. Foreigners, again, dressed differently from the Venetians.

Consequently, if, during a celebration like the Saturnalia, people of different classes were to swap roles, they also had to change their dress. Dressing up — or down, or even cross-dressing — therefore became a part of the Saturnalia.

The Saturnalia happened largely in the streets and in other public spaces, and they were rowdy affairs, where the social order didn’t exact break down, but to many it must have looked like it did.

This fiddling and playing with an otherwise very rigid social order also functioned as a kind of safety valve for the social tensions, which such an unequal society inevitably generates.

Associated with winter solstice, the Saturnalia was also about darkness and light, about the turning of time, and the start of a new cycle of life.

In that sense, it was a kind of New Year’s feast. The old solar year was ending, and a new one was starting, and the cycle of nature and the cosmos started all over again.

When Christianity became dominant, and powerful, they wanted the Saturnalia gone, and the early church did that by placing Christmas on top of it.

The time of the birth of Christ is not specified in the Bible, and by placing the celebration at winter solstice, the church effectively prevented people from just celebrating both, to hedge their bets with the divine.

One of the doctrinal problems of the early church, was that they tried to insert a monotheistic faith into a world, which had always been polytheistic.

When a new religion and a new divinity arrive in a polytheistic culture, it is easy for people to just join the new god to the existing pantheon. The more, the merrier, and what difference does one more god do when you already have hundreds. Not knowing which divinity is the more powerful, people just worship them all, as far as possible.

Such behaviour is, of course, anathema to core Christian beliefs, and one way of stopping it, is to place Christian places of worship on top of the Roman, and likewise in the calendar.

Christmas in December was therefore all about preventing people from celebrating both Saturnalia and Christmas.

Consequently, Saturnalia disappeared in the 400s and 500s, as Christianity became dominant in the Roman world.

Some bits persevered, and became part of the later carnival, such as the playing with the social order, rowdy and noisy feasts in public spaces, and dressing up, down, cross, whatever.

Farewell to meat (and fun)

The other root of the carnival are more Christian, or maybe even Jewish.

Easter has forty days, as the resurrected Christ spent forty days on earth before ascending to the heavens.

Easter, of course, is derived from Jewish Passover, which also has forty days, but before the celebration, not after.

The forty days before Easter became Lent, a period of abstinence and penitence before the great events of the Christian religious calendar: the crucifixion and the resurrection, the sacrifice and the defeat of death.

During Lent, the basic rule was — maybe a bit simplified — that if it’s fun, it’s forbidden.

Therefore, no meat, no sweets, no rich pastries, no wine, no parties, no dancing, no sex.

For all those, who enjoy some of all that — and who doesn’t — Lent will be like a very long funeral.

It should therefore be of little surprise, that fun-loving people, in the time leading up to Lent, would try to have a blast, and indulge, and overindulge, in all those things, which would soon be proscribed.

Now, Easter is a moving feast. It takes place on the first Sunday after the first full moon after spring equinox — just how very pagan is that! — so it can shift back and forth of more than a month.

Easter can be just after the spring equinox, around March 22nd, if that happens to be a Sunday with a full moon, or it can be an almost full lunar cycle (28 days) and almost a full week (six days) later.

Consequently, the start of Lent moves back and forth the same way, so it can be in early February or half-way into March.

Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, just to set the tone, and since meagre times were ahead, the period before became the fat week — and especially the Tuesday, Shrove Tuesday in English, but Fat Tuesday in most other languages, such as mardì gras in French, and martedì grasso in Venetian and Florentine.

The fat week because it was the last chance to eat all the rich, fatty foods which would soon be proscribed.

The name used for this period of one week, or sometimes ten days, leading up to Lent, reflected the soon to come deprivations.

The word ‘carnival’ probably comes from Latin, either carnem levare — the removal of meat, from the diet, it is understood — or from carne vale — goodbye to meat.

Carnival follows the Christian liturgical calendar, but it is emphatically not a religious feast. If anything, it is a counter-reaction to the impositions of the church calendar.

The Venetian version of carnival

Carnival is therefore a fusion of surviving remnants of the Roman feast of the Saturnalia, and the desire to enjoy life a bit before Lent.

In Venice, there must have been a carnival in the earliest times.

The first mention of the carnival in a surviving Venetian document, is from 1094, during the reign of doge Vitale Falier.

In 1296, Shrove Tuesday — the last day of the carnival before Lent — was made a public holiday.

The Venetian carnival was not, however, limited to one week or to ten days.

The official start of the carnival in Venice was on St Stephen’s day, the 26th of December.

The Venetians happily did up to two months of carnival.

Most of the carnival in Venice was private, in the form of feasts, events and celebrations organised by the wealthy or by communities.

Large masquerade parties took place in various public squares. The large Campo Santo Stefano was venue for such an event, on December 26th, the opening of the carnival.

Many other parties were hosted in the palaces of wealthy nobles, or in the Ridotto, a palace on the Grand Canal, close to San Moisè, which functioned as a kind of state sanctioned casino for a long time in the 1600s and 1700s.

Starting in the early 1600s, stable theatres, as we know them, with dedicated buildings, started appearing in Venice. Theatre season also began on December 26th, and the theatres became an important part of the carnival entertainment scene.

In the theatres, the less affluent watched from the floor, while those who could afford it, bought the key to a palco — a separate cabin, so to say, on one of the balconies. These palchi were so private, that literally everything happened in there during the plays.

As most occupants of the palchi were masked, nobody knew who was with whom in which palco. The famous Venetian courtesans were no doubt frequent guests there, hidden behind carnival masks.

All this made the Venetian carnival a major tourist attraction, which in turn fed the madness of feasts, music, theatres, gambling, money-lending for the same, prostitution and what not.

People bring money, and money attracts more people, so street artists of all sorts gravitated to Venice for the carnival. Street theatres, tightrope walkers, jugglers, magicians, fortune-tellers and such were all over.

John Evelyn

The English gentleman John Evelyn spent almost a year in Venice and Padua, between 1645 and 1646. He was on the Grand Tour, ostensibly to study and learn, so he spent quite some time in Padua, but there was no not going to Venice for carnival.

This bit from his diary gives a good impression of how it was:

I stirred not from Padua till Shrovetide, when all the world repair to Venice, to see the folly and madness of the Carnival ; the women, men, and persons of all conditions disguising themselves in antique dresses, with extravagant music and a thousand gambols, traversing the streets from house to house, all places being then accessible and free to enter. Abroad, they fling eggs filled with sweet water, but sometimes not over-sweet.

They also have a barbarous custom of hunting bulls about the streets and piazzas, which is very dangerous, the passages being generally narrow. The youth of the several wards and parishes contend in other masteries and pastimes, so that it is impossible to recount the universal madness of this place during this time of license.

The great banks are set up for those who will play at bassett ; the comedians have liberty, and the operas are open ; witty pasquils are thrown about, and the mountebanks have their stages at every corner.

The diversion which chiefly took me up was three noble operas, where were excellent voices and music, the most celebrated of which was the famous Anna Rencha, whom we invited to a fish-dinner after four days in Lent, when they had given over at the theatre. Accompanied with an eunuch whom she brought with her, she entertained us with rare music, both of them singing to a harpsichord. It growing late, a gentleman of Venice came for her, to show her the galleys, now ready to sail for Candia.

This entertainment produced a second, given us by the English consul of the merchants, inviting us to his house, where he had the Genoese, the most celebrated base in Italy, who was one of the late opera-band.

This diversion held us so late at night, that, conveying a gentlewoman who had supped with us to her gondola at the usual place of landing, we were shot at by two carbines from another gondola, in which were a noble Venetian and his courtezan unwilling to be disturbed, which made us run in and fetch other weapons, not knowing what the matter was, till we were informed of the danger we might incur by pursuing it farther.

Stuff happened in Venice during Shrovetide.

There are a few things in here, which we haven’t covered yet.

We need to talk about masks, about bulls and the competitions of the youths of wards and parishes.

Some of the figures

How did people dress up for carnival?

For a great many persons, especially from the more affluent classes, masking was not to pretend to be somebody or something else. It was for anonymity.

The most common masks were therefore not the figures of the commedia d’arte or mythological figures, or something like that. Rather, they were anonymous, alike the others, while hiding the wearers’ identity.

A common costume was the bauta. It consisted of a simple white face mask, called the larva, with a triangular protrusion in front of the mouth, which allowed the wearer to eat and drink, and to speak, but with a distorted, less recognisable voice. Over the mask, a shoulder long hood, a short cape to the elbows, and a longer cloak to the knees. A tricorne hat finished the outfit.

The bauta was worn by men and women alike, but women had a few more choices.

Sometimes, women wore a similar outfit, but with a more feminine mask, which covered the whole face, without the protrusion in front of the mouth.

Another female costume was the moretta, which in its simplicity was a round piece of black velvet, which covered the face. It had two slits for the eyes, a string around the head to hold it in place, and a button sewed on the inside, which the wearer held in her mouth.

It was therefore a silent figure, as the woman couldn’t speak and hold the mask in place at the same time, and it is sometimes called the servetta muta — the mute maid.

These costumes are all about hiding your identity, rather than assuming another identity, and while they were much used during carnival, they were not exclusive to the carnival. Especially the bauta was used by the nobility throughout the year, to be able to socialise anonymously.

A not so silent figure was the gnaga, which is quite odd. The gnaga was a parody of a lower class cat-woman, and the wearer was usually a man. It consisted of a simple dress, as commoner women wore, with an apron, and a cat-like mask. Often, on the arm, the figure carried a handbasket with a live kitten.

Sometimes, the gnaga figures went around the city, shouting abuse at others, to comical effect, but sometimes getting shot at in return, or they simply meowed like a cat, instead of speaking.

The gnaga figure is a typical example of how the memory of the Saturnalia lived on, with its play on social norms and customs.

In the show notes on the website, I have put some images from the 1750s of some of these figures and costumes.

Giovedì grasso

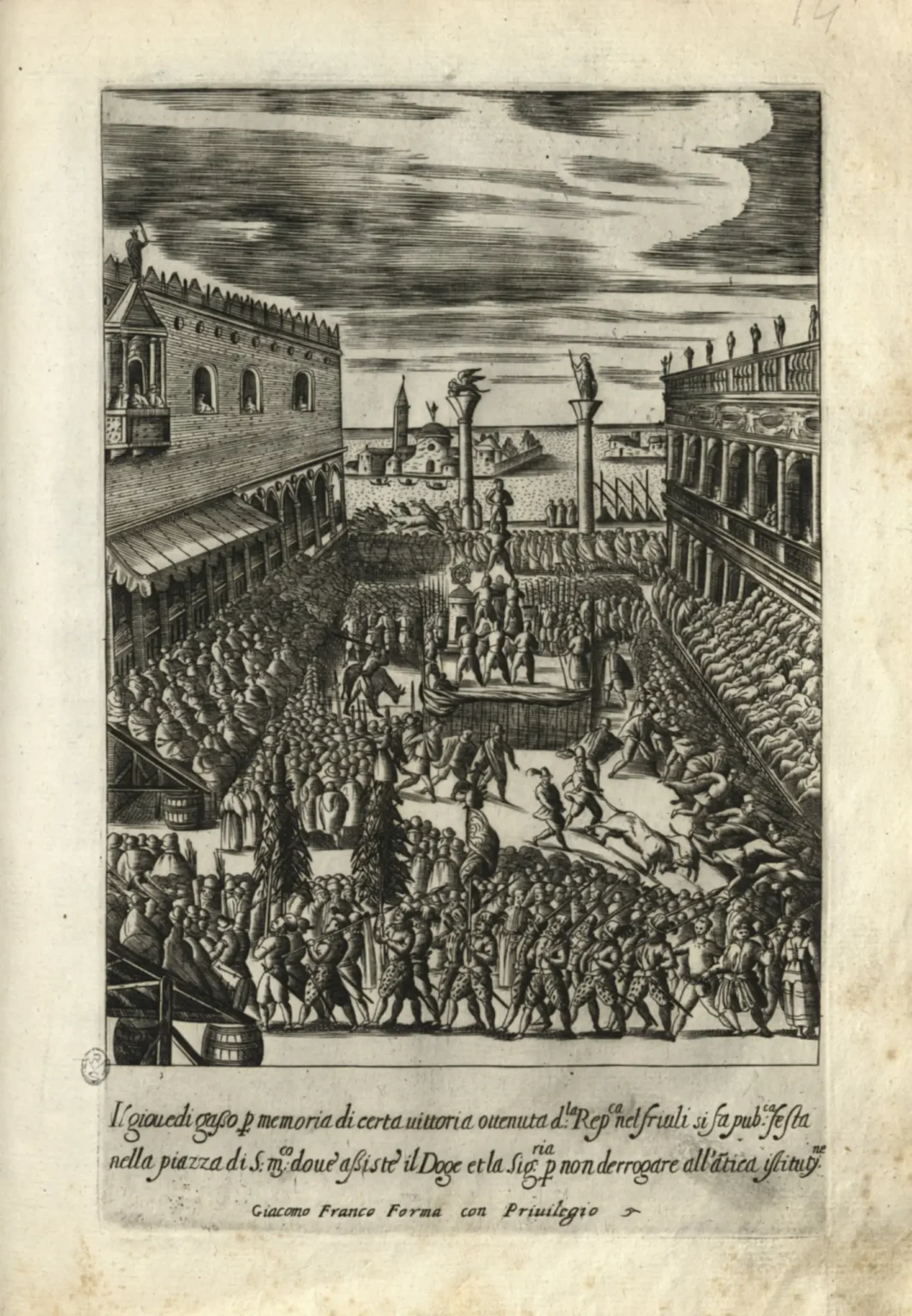

While most of the carnival activities were private, there was one major state event during carnival, and closely associated with it.

It was, for most people of the time, the defining event of the Venetian carnival, and John Evelyn hints at it in the earlier quote. The mention of bulls running in the streets, and of competitions between commoners, are references to the feast of the Giovedì grasso.

Fat Thursday — Giovedì grasso — is the last Thursday before Lent, and the Venetian celebration had very little to do with the carnival, except for the coincidence of the dates.

During the celebration, in various periods, people chased pigs in the alleyways, the doge smashed wooden models of castles with clubs, bulls were executed by decapitation or chased by dogs, people build human towers several storeys tall, funambulists delivered flowers to the doge, and fireworks, lots of fireworks.

So, what was this magnificent, if rather odd, event?

It was, in all its simplicity, the celebration of a military victory over a church prelate.

Patriarch on patriarch

In the mid-1100s, the Holy Roman Empire and the Pope fought a prolonged conflict. The two sides are usually referred to as the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. The emperor was Frederick I Barbarossa, and the Popes Adrian IV and Alexandre III.

The multiple wars included most of the Northern Italian communes, some aligned with the empire, some with the Pope.

Venice mostly kept out of the fight, and in 1177, the republic would be the peace mediator, but in 1159, Venice had recognised Alexander III as the real Pope, and not the anti-pope Victor IV, supported by Barbarossa.

Therefore, in 1161, Barbarossa instigated several of his supporters among the North Italian city states to attack Venice. Ferrara, Padua and Verona were among the cities, who initiated hostilities with Venice.

Another of his vassals, the Austrian Ulrich of Treven, Prince-Patriarch of Aquileia in Friuli, saw an opportunity to even some accounts with the nearby competitor, the Patriarch of Grado, which was on Venetian territory.

The double patriarchy, contesting the same diocese, was something, which went back to the invasion of the Lombards in the 600s. It was therefore a rather old conflict, which flared up again.

In February 1162, during carnival, the troops of Ulrich of Treven attacked and took Grado. The Venetian Patriarch of Grado, Enrico Dandolo, fled to Venice.

Ulrich of Treven might have thought he was covered by the other fights Venice had to the south, with Ferrara and Padua, but Venice showed itself capable of fighting more than one war at a time.

The doge, Vitale Michiel II, went with a fleet north, and on Fat Thursday, he retook Grado in a surprise attack.

Not only did Venice retake the territory lost, the Venetians also captured the Patriarch himself, twelve of his canons, and a large number of his vassals. The Venetian forces surged forward, and took and demolished numerous castles belonging to vassals of Ulrich of Treven.

The prisoners were taken to Venice, and paraded around the city in triumph.

A bull, twelve pigs and twelve loaves

The price, which Venice demanded for the release of the Patriarch of Aquileia and his canons, was a tribute, to be paid annually on the day before his capture.

Early documents give the tribute as twelve fat pigs and twelve loaves of bread, but it very soon became one fat bull and twelve pigs, representing the Patriarch and the twelve canons.

The animals arrived each year on (Fat) Wednesday, and were kept in the courtyard of the Doge’s Palace.

Inside the palace, the Doge and the Signoria went to the Sala del Piovego — the main courtroom on the first floor — where they smashed models of castles with large clubs, in a symbolic re-enactment of the war of 1162, and the destruction of the castles in Friuli.

Then, in a kind of mock trial, the animals — symbolising the defeated enemy — were sentenced to death.

What actually happened to the animals seems to have changed over time.

Initially, from what we can gather, the pigs were slaughtered, and the meat distributed to the senators of the republic, while the loaves of bread were given to the prisoners in the Doge’s Palace, which also housed courtrooms and prison cells.

The bull — and at times also the pigs — were killed in the square in front of the palace, by decapitation, public execution style.

It also seems that, at least in some periods, the pigs were released in the alleyways for people to catch, and then supposedly eat. This would be a certain way of getting a popular participation in the event. It would be quite a spectacle, and free food for the lucky ones.

But, as always, we don’t really have precise and reliable sources for such almost mythological medieval events, so we cannot draw up an exact timeline of what the Venetians did when and in what order.

What definitely did happen for several centuries, was that animals arrived, and became part of a celebration of the victory on Fat Thursday — Giovedì Grasso — which took place in the Piazzetta — the part of the square facing the Doge’s Palace.

Over time, the celebration found a regular form, and at least from the 1500s onwards, we have a fairly good idea of how it was.

The smashing of wooden castles with maces stopped.

When Andrea Gritti was made doge in 1523, he abandoned this part of the celebration. Apparently, as a military leader with real-life experiences of taking cities, he found the whole thing ridiculous and beneath him.

A celebration of state

The feast took place in the space between the Doge’s Palace, the Basilica, the two columns, and the Marciana Library.

If you’ve ever been to Venice, you’ve been there.

Spectator tribunes were constructed in front of the palace and opposite, with three or four rows of seating, destined for the senators and magistrates of the republic.

The doge, the Signoria and other of the highest offices of state looked on from the loggia on the first floor of the Doge’s Palace, or from the balcony on the second floor.

In the middle of the square, a stage was constructed, and at times also a tall wooden tower, symbolising a castle.

In the morning, people were let into the square, but everything kept under strict control by the armed arsenalotti, the armed guards of the Arsenale, the Venetian navy docks. The arsenalotti were the trusted security force of the Republic of Venice.

First, the bull — symbolising the defeated Patriarch — was decapitated in front of the crowds.

The man wielding the sword, was a blacksmith, as the blacksmiths had performed well in the battle of Grado. This is a bit like the box-makers and the battle for the donzelle, discussed in the previous episode.

One of the strongest members of the guild of the blacksmiths got the honour, and arrived with the sword, dressed in his finest.

It was a blunted two-hand sword, and the head of the bull had to come off in one blow, but the blade was not allowed to hit the ground, despite the force needed to decapitate a bull in one blow.

One of these swords is on display in the armoury in the Doge’s Palace.

As the bull — the Patriarch — fell dead to the ground, the crowd clapped and cheered.

Then, a funambulist walked a right-rope from a boat moored at the pier all the way up to the top of the bell-tower, and then down towards the doge on the balcony of the palace. He handed the doge a bouquet of flowers, and made his way back to the tower, and the boat again, with the crowds clapping and cheering below.

This tradition seems to have started sometimes in the early 1500s, with a Turkish tightrope walker, so it was called the ‘Flight of the Turk’. One year, the funambulist fell and died, and afterwards they used either a contraption with a man hanging off the rope by two iron rings, as if flying, or a kind of mechanical dove, which spread confetti and flowers along the way over the crowd.

The name became the ‘Flight of the Angel’ or the ‘Flight of the Dove’.

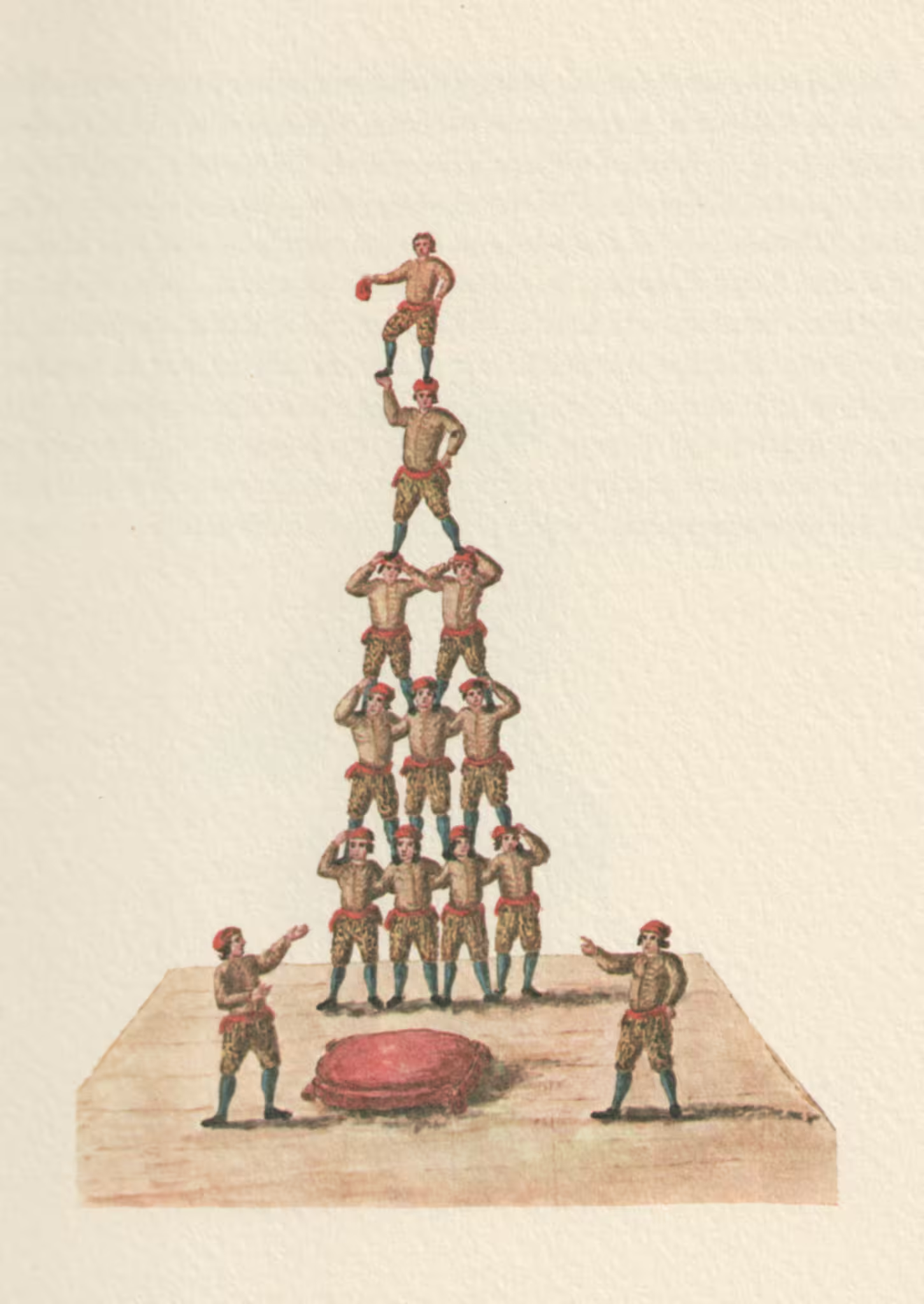

The next event was the Forze d’Ercole — the Strengths of Hercules or the Trials of Hercules.

Two groups of commoners, the Nicolotti and the Castellani, competed in trials of strength and endurance. The Nicolotti were from the part of the city south of the Grand Canal, and had their name from the church of San Nicolò dei Mendicanti, while the Castellani were from the northern side, their name either from the sestiere Castello, or from the fortifications which existed there in medieval times.

The Forze d’Ercole was a human tower. A group of strong men formed a base, and others climbed up to stand on their shoulders. Sometimes, sticks and planks were used to create new intermediate bases, on which the next level could stand.

This continued, until the structures were four, five and six levels tall. At the end, a young agile man climbed all the way to the top, and stood there alone, waving a flag. Sometimes, another one would follow, and do a headstand on the first guy’s head.

The group, who got the highest and stayed up for the longest, won.

Such human towers were made for other occasions too, for example at the arrival of foreign heads of state. At times, they made them on the Grand Canal, on platforms created across two large boats.

Another show of force between the two groups, were group fights with fists or sticks, and such battles happened too, during the Giovedì grasso.

At other occasions, they were fought on bridges in certain parts of town, where we still have names like the “Bridge of Fists” and the “War Bridge”.

Money for the feast

By the mid-1400s, Venice had conquered the mainland and also the Patriarchy of Aquileia. The ancient conflict between the two patriarchies was thereby solved, as they were now both Venetian dominions.

It therefore made little sense for Venice to demand a tribute of submission of an entity, which they now controlled.

After almost three centuries, the celebration was deeply entrenched, and it couldn’t be abandoned, so the republic picked up the bill.

In practise, the task of funding and organising the feast fell to the Rason Vecchia — literally the “Old Bookkeeping” or “Old Accounting Office”, if we want to give it a more modern sounding name.

As a curiosity, I stumbled over some of the old paperwork, and would like to share a bit of this bureaucracy with you. It is both very ancient and quite modern, at the same time.

Here’s the order to pay the head of the Castellani for their part of the show:

On the day 15th September 1766

Constituted Carlo Nigrinoti son of Francesco, lives at San Luca, ship carpenter, and Zuanne Pasinello, companion of Paolo, lives at San Siminiano, stonecutter, as those, who by His Excellency Zuan Battista da Riva, Procurator Treasurer of the present most Excellent Magistracy were chosen as Head of the Castellani to do the show of strength in the public St Mark’s Square for Fat Thursday next upcoming of 1766 in front of His Serenity, promising and obliging themselves to do six different games with their Company, conforming to the usual, for the price of twelve Ducats of six lire and four soldi to the ducat, and the present constituted shall participate with the impresario of the scene.

Carlo Nigrinoti signed twice for both, as the other didn’t know how to write.

The date of the celebration was given as in 1766 because it was in February, and therefore still in the same year of 1766, more veneto.

Another document instructs the keepers of the Arsenale to hand out forty clubs or maces to the two heads of the Castellani, of which ten of good quality and appearance, to be returned in full after the event.

There are two almost identical documents for the Nicolotti.

Yet another contract hired one Piero Bailo to do the flight above the square, from the boat to the tower to the palace, deliver the flowers to the doge, and return as he came, for the same amount of twelve ducats.

Being just one, he clearly earned a lot more money, unless the pay also includes the expenses for rigging up the lines and safety measures.

It is signed “I, Piero Bailo, affirm and I oblige myself as above.”

This paperwork was made months before the event.

The end of the carnival

The Venetian carnival continued, as it always had, until 1797.

The republic got run over by Napoleon in May 1797, and he sold the city to the Austrians later that year.

The Austrian troops occupied the city in January 1798, and not wanting trouble with their new underlings, who hadn’t consented in any way to live under Austrian occupation, the carnival didn’t happen.

If there was one thing, the new Austrian rulers did not want, it was having Venetians, and God knows who, roaming the city at night, masked, unrecognisable and possibly armed.

As Venice was passed from the Austrians to the French, and back to the Austrians again, that line of reasoning didn’t change. The rulers didn’t like the carnival, and even if some people privately had parties, it never really recovered.

Some local celebrations on the islands of Murano and Burano lingered, but in Venice the grand, months-long carnival, which had attracted tourists and hustlers for centuries, mostly ended with the Republic.

The modern carnival

But, Venice has a grand carnival today.

The modern carnival started in the 1970s.

Locals, mostly to entertain the children, started organising carnival celebrations around the city. Tourists soon joined in, the city administration took over the organisation, and within a decade, it became yet another tourist event in the already overfull Venetian calendar.

As the events got larger — without any roots in the local communities, but taking over the shared spaces — many Venetians gave up on the carnival.

This is a common theme here in Venice. As the tourists enter, the locals leave.

Community events without the community are just events, and in this city cursed by Mammon, that means commercial events for the economic benefit of mostly outsiders.

Consequently, often those, who live in the worst afflicted areas of the city, and who have the possibility, leave the city during the carnival.

This is, unfortunately, a dying city, where the interests of those who don’t live here, count for much more than the interests of those who do.

Now, my apologies.

It wasn’t my plan to end this episode on a sad note, but sometimes living in Venice is sad. It is a place in mortal decline.

For more of the reasons for it, please listen to episode nine: Subject city.

Leave a Reply