Intro

The Serenissima produced and exported treacle, both to Western Europe and to the Ottoman Empire. It was a flourishing business for centuries, and an important part of the Venetian economy. Venice treacle, however, wasn’t some sweet sugary substance. It was an ancient medicine, which supposedly could prevent or cure almost anything.

Links

Images

Transcript

Episode 23 — Venice treacle — the cure-all remedy

In the past episodes on the plague in Venice, there were doctors going on house visits to sick patients, dispensing preservatives and cures.

Venice treacle was — or so it was believed — the best preservative, cure and restorative for the plague.

The English word ‘treacle’ is a distortion of the real name of this medicine, which was Theriaca. Dear child has many names, so we have numerous variations, such as theriac, triaca and treacle.

Theriac wasn’t a Venetian invention, but in the Middle Ages, thanks to its privileged trading position between the east and the west, Venice acquired both the knowledge, the skills and the wealth required to produce Theriac.

Add to this the Venetian marketing skills, and “Venice treacle” became an unrivalled brand for centuries.

Other nations made Theriac too, but the Venetian brand remained strong well into the 1700s.

A Theriac advertisement

So what was Theriac, and what was it good for?

Let’s have a look at how the Venetians sold it. The following is from a flyer from a Venetian pharmacy, the Speziaria al Paradiso on the Riva del Vin close to the Rialto bridge, printed in Venice in 1688.

The flyer is bilingual English-Venetian, so clearly intended for foreigners, and Englishmen in particular.

I found this specific flyer online in the Wellcome Collection, so it, along with many others, made its way to England, to end up in the collections of a research library.

The title of the flyer, wrapped around the shop sign of the pharmacy, reads:

Theriaca Andromachi senioris divinum inventum.

Theriac was invented by Andromachus the Elder, physician to emperor Nero in the first century, but the flyer implies supernatural assistance.

This is not a normal medicine. It is ancient and it is divinely inspired.

The introduction goes:

The above-said antidote is composed in Venice with all diligence and care by Francis Raffaeli Apothecary at the sign of the Paradise at Rialto upon the wine bank in the presence and before the most Illustrious Magistrates of the Old Justice, and the most Excellent College of Doctors, and of the Apothecaries, and other deputies for the same, the faculties, and rare virtues of which are as follows for the good of all people.

Here the “wine bank” is a rather hapless translation of the name of the street, the Riva del Vin.

The “Old Justice” — the Venetian Giustizia Vecchia — was an ancient magistracy of the Republic of Venice, which oversaw the business practices and product quality of most Venetian artisans and crafts.

This is the Venetian state controlling and certifying the production methods and quality of the Theriac, which is a testament to the importance of this product for the country itself.

The “College of Doctors and Apothecaries” — the Collegio de’ Medici e de’ Speziali — was the industry association, which, like the state, controlled and guaranteed the quality of the product.

This is therefore not a single shop selling an artisanal product. It is rather a national endeavour, where the pharmacy is but a single cog in a much larger wheel.

If anybody thought it was a recent thing that states and industry associations control and regulate the affairs of individual, private businesses, well, think again. This text is over four centuries old.

Our modern society has very deep roots.

Now, let’s move on to the panegyric of Theriac. These people had things to sell, and sell they did.

Much of this will make little sense, unless you’ve listened to episode 17, about humours, complexions, miasma, malignant air, and such.

The Treacle amongst all the other prerogatives has virtuous preserve from the plague, and from any other Contagious Sickness; Keeping the body cheerful and in health.

It is good against the passions of the heart, or heart aching, removing thence Melancholy, Consuming the putrefied humours of the body expelling every unwholesome superfluity of the Same, Keeping it wholesome, and strengthens it admirably.

It cures the very plague, and other pestilential deceases.

These are clearly the main selling points, and probably also reflects what were the main fears of the clientele: plague and cardiovascular conditions.

It is good again all bitings of all sorts of venomous creatures. Especially of the scorpions and mad dogs, and other sorts both of the land and water, taken, at the mouth and applied to the wound on the outside.

It preserves from poisons, taken before or when there is suspicion, and Especially after the poison is discovered, in which case the sick person must Endeavour to vomit often taking the said treacle inwardly.

Poisonous animals are easy to understand, but any ailment which didn’t have evident external effects on the body, was considered caused by poisoning.

Consequently, the doctors of the past considered many conditions, which we wouldn’t consider cases of poisoning, as such.

It helps very much those that from an inward, and unknown disease, consume away as if they are poisoned.

One could imagine this is about depression, or psychological trauma of some kind, or maybe autism.

It is singular remedy against all aches, preventing, the trembling Rigour, and colds that continue long, taking this treacle, three, or four times before the fits begin.

I guess this could be anything which causes a fever, shakes or trembles of some kind.

It cures the quartan ache given in the universal state of the fit, but not in the beginning the matter, and cause being raw.

The quartan fever is a fever which occurs every four days, usually a type of malaria.

The ‘matter’ being ‘raw’ refers to miasma in the body, that is, the external matter which has entered the body to cause a disease.

Fevers such as malaria were associated with miasma and malignant air. In fact, the name malaria literally is mal-aria, malignant or bad air.

It preserves from pestilent and malignant aches, and cures them.

This could be anything. Whatever your ailment, Theriac is the remedy.

It expels the wind from the stomach, stops spitting of blood taken by the persons grieved inwardly.

It expels phlegm from the stomach, it is good against the pain in the entrails, griping of the guts, pain in the reines, occasioned from ulcers, the stone, it cures the Dropsy, and the Prissique, in the beginning of the fits.

Gibberish, apparently.

Phlegm is one of the four humours, and the least well-defined of them.

The ‘reines’ are the kidneys, as in ‘renal’.

Prissique is consumption or tuberculosis.

It strengthens the eye sight, and is excellent good for all internal diseases of the head, falling sickness, apoplexy, Palsy, stops the flux, and Rheumes provoking sleep.

It is good against the pains in the brest, coughs, and Catarrhs.

It’s good for everything, really. Buy Theriac!

It comforts admirably the heart, prevents the burning, and quacking thereof.

The English text literally says ‘quacking’, but the Venetian says palpitations.

It cures all indispositions of the stomach, as extreme hunger, or loathness and strengthens the Vital parts.

Too much appetite? Theriac’s the remedy. Too little? Theriac’s the remedy.

One wonders what the ‘vital parts’ are? What are they selling here?

They’ve already mentioned most internal organs.

It Kills all sorts of vermin, or worms; expels them our of the body, and hinders their ingendring.

Worms must have been a much larger problem then, than it is in our times, to be worth mentioning.

The ‘ingendring’ from the original means generation, rather than reproduction. This is evident from the Venetian text.

It was a common belief that some animals were generated spontaneously if the external conditions were right. They didn’t reproduce, they just appeared.

Spontaneous generation was also how miasma came about.

It cures the leprosy used often by the patient.

Leprosy is another terror, which we have luckily left behind, at least in the richer parts of the world.

It provokes womes flowers, and the stopped flux of the haemorrhoids, and what is wonderful it equally restrains the over much flux of the same, comforting nature, weakened by both indispositions.

The ‘womes flowers’ is either a very inept or a very prudish translation from the Venetian, which clearly states “the menstruation of women”.

Whether the intention was to say “women” or “womb” is not entirely clear.

It provokes the afterbirth, and it helps to bring forth dead children, it has many other, rare virtues, that for, brevity sake do not write, it being, a most rare, and Real medicine, and well-known by all the world, it agrees to all ages above seven years, and to all Complexions, and may be given at, or in any season.

Women’s health appears as a bit of an afterthought, even if one of the main causes of death for women was childbirth.

Still, problems around childbirth and stillborn fetuses must have been sufficiently common for them to appear here.

THE DOSE

To the young, and those of strong Complexions the weight of two, or 3, scruples alone, or in wine, or aqua mulsa, or other liquor.

The aged people one dram, and the same weight to be given, for poisons and the plague.

A scruple is an apothecary’s measure, corresponding to about 1 gram, while a dram is three scruples, or around 3 grams.

The term ‘aqua mulsa’, which hasn’t been translated from the Venetian, is honey water.

A universal remedy

So, according to the sales materials, Theriac supposedly cured just about anything.

It was practically a universal remedy.

The Venetians didn’t invent Theriac. As the flyer clearly states, it is an ancient remedy, ascribed to Andromachus the Elder.

He was the personal physician of emperor Nero, which must have been a fairly stressful job.

Theriac therefore goes back at least to the first century, in Roman times.

Andromachus, however, didn’t start from scratch. He elaborated on an older remedy, called Mithridatium.

King Mithridites IV of Pontus, two centuries earlier, was fearful of being poisoned.

The Kingdom of Pontus was on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), and Mithridates IV ruled at a time when Rome was expanding in the East.

He had his physician make a concoction from all the known remedies for all the known poisons, which Mithridates then took regularly as a preservative against poisoning.

This was Mithridatium — a universal antidote for all poisons.

Legend has it, that when Mithridates was defeated in battle by Pompey the Great, he tried to commit suicide by poison, but it didn’t work because he had regularly taken Mithridatium, so he threw himself on his sword.

The alternative to suicide for a defeated enemy of Rome, was becoming a prop in Pompey’s triumphal procession back in Rome, after maybe years in a dungeon or in a cage somewhere, to be unceremoniously garotted in public as part of the entertainment, the triumphant victor offered the crowds.

Sometimes — much too often, in fact — civilisation is not very civilised.

Anyway, Pompey heard rumours of this miracle antidote, and had all the spoils of war searched for the recipe.

This way, it found its way to Rome, and later to Andromachus the Elder. He made numerous additions to the recipe, most importantly, the flesh of vipers.

His Theriac would be a staple for the emperors after Nero, and many of them took it, like Mithridates, as a preservative against disease and poisoning.

Galen of Pergamon was one of the most renowned physicians of Antiquity, and in the second century he wrote, among much else, a treatise on Theriac, which included a detailed recipe written as a poem, to make it easier to memorise.

His writings were copied throughout the Byzantine Empire, and found their way into the Arab world too.

The writings of Galen were foundational for the development of medicine in medieval Western Europe, and the texts arrived from Constantinople and from the Arab world, in Greek and Arabic.

Venice was in many ways the bridge between emerging Western Europe on one side, and the Byzantine Empire and the Caliphate on the other side.

The ancient knowledge came to Western Europe from the Greek and Arab worlds, and it mostly passed through Venice.

Therefore, Venice had the contact network, the knowledge, the practical skills, and the money to take up Theriac production before everybody else.

A remedy for kings and emperors

And money was a concern.

Theriac has been called an imperial medicine because only an empire could make it.

There are over sixty ingredients in the recipe, and they come from three continents. While most are found in the Mediterranean area, there are ingredients on the list from China, India, Persia, Pontus, Judea, Ethiopia, Egypt and many other places.

The ingredients were primarily:

- Sea onion, a Mediterranean plant

- Viper flesh

- Long pepper

- Rose petals

- Dalmatian iris

- Rape seeds

- Water germander

- Cinnamon

- Agarikon, which is a mushroom

- Myrrh

- Indian costus

- Saffron crocus

- Chinese cinnamon

- Spikenard from the Himalayas

- Lemongrass

- Incense

- Black pepper

- Cretan dittany

- Marrubium

- Rhapontic rhubarb

- Spanish lavender

- Parsley seeds

- Lesser calamint

- Ginger

- Creeping cinquefoil (sink-foil)

- Felty germander

- Ground pine

- Stone parsley

- Baldmoney

- Valerian spikenard

- Golden spikenard

- Wall germander

- Malabathrum from India

- Gentian root

- Aniseeds

- Balsam fruit

- Fennel seeds

- Cardamom from India

- Seseli

- Pennycress

- St. John’s wort

- Gum arabic

- Bishop’s flower

- Castoreum, that is, scent glands from beavers

- Pipewine

- Athamanta

- Opopanax, a gum resin

- Feverfoullie

- Opium from Egypt

- Liquorice juice

- Nutmeg oil

- Terebinth, a resin

- Storax, also a resin

- Iron vitriol, a mineral

- Hypocistis

- Lemnian earth, from the Greek island of Lemnos

- Acacia juice

- Sagapenum, a resin from Persia

- Dead Sea bitumen, naturally occurring asphalt

- Galbanum, also a resin gum

- Skimmed honey, and

- Malvasia, a Greek wine.

How many of them have you ever heard of?

The speziali — the apothecaries — were also the forerunners of chemists and botanists. They had incredible knowledge about plants and their effects on the human body.

Some of these substances were prepared beforehand, in the shape of dried pellets. There were three such pellets in the recipe, of sea onion, viper flesh, and a mixture of herbs called Hedychroum or Hedicroi in Venetian.

Most of the dry ingredients — pellets, seeds, dried plants and such — were ground to a fine powder. The various resins and gums were dissolved, and the powdered ingredients, the liquid elements and the gums and resins were finally mixed, and then combined with skimmed honey and wine to form an electuary.

An electuary is something like cough syrup. A sweet, sticky substance to help the rest go down.

The original name of Theriac became treacle in English, before treacle came to mean a sweet, sticky substance.

The finished mixture was poured into jars of tin or glazed earthenware, and carefully sealed with the mark of the pharmacy under the gaze of the authorities.

For the following eight days, the jars were shaken regularly, and then left to ferment and age for at least six months. It was illegal to sell it earlier, but Theriac was believed to be at its most potent after six years, and still good after forty years.

Three jars of each batch were handed over to the authorities as a control sample, so they had a comparison, in case there were later suspicion of the lot having been tampered with.

John Evelyn

The advertising flyer from the start of this episode noted how the Theriac was produced under the control and supervision of both the state authorities, and of the College of Doctors and Apothecaries.

What the flyer didn’t mention, was that the production also took place out in the street, in front of, or near the pharmacy, surrounded by a crowd of curious onlookers.

John Evelyn, an English gentleman, went on the Grand Tour in the 1640s — probably to get a bit away from a rather stressful atmosphere in London — and he spent almost a year in Venice and Padua from April 1645 to March 1646.

When he left, he had more stuff than when he had arrived. From his diary for late March 1646, when he was leaving:

Having packed up my purchases of books, pictures, casts, treacle, &c., (the making and extraordinary ceremony whereof I had been curious to observe, for it is extremely pompous and worth seeing) I departed from Venice …

Venice was of course one of the places in Europe to get books and works of art, but he also bought treacle to take back home.

It was a sought after and valuable product, and Venice treacle was believed to be the best.

It is interesting, however, that he already knew about the extraordinary ceremony around the making of it, and that it was on his list of things to see in Venice because it was extremely pompous and worth seeing.

The making of Theriac was a show, and a well-known show people came for and wanted to see. It was an experience, one of those things you’d had to do when in Venice.

Today, you haven’t been to Venice if you haven’t taken a gondola ride. Then, you hadn’t been to Venice, if you hadn’t seen the Theriac show and bought a sealed jar of the universal remedy to take back home.

The Theriac Show

Due to the nature of the product, the apothecaries tended to make large batches, once or twice each year.

Sourcing the inputs was complex. Some ingredients came from far away, and depended on the annual cycle of the Venetian merchant fleet. Others were by nature seasonal, such as vipers and many plants, even if they were sourced locally. Finally, some had their own long production cycle, for example the three types of pellets, which had to be produced beforehand.

This, combined with the requirement of long-term fermenting and seasoning of the mixture, made it more practical to do just a few production runs each year, in large quantities.

The most popular periods were in May and August.

Large batches required many labourers, working the huge bronze mortars pounding the ingredients into a fine powder, and other workers continuously sifting the ground materials to get only the very finest grains.

The logistics of managing these work crews were complicated, and as there wasn’t sufficient space and light inside, the work was done out in the open.

Working outside also became a requirement of the authorities.

To avoid cheating, such as omitting or substituting expensive or difficult to obtain ingredients, or speeding up slow processes like the fermentation, there were strict rules for how the production happened.

Now, it goes without saying, that such rules and controls tend to happen because some people were cheating, damaging the others or even putting lives at risk.

After all, most of the rules we have today for safety in the workplace, for pharmaceuticals, for children’s’ toys and much more, have been paid dearly in blood. Few such rules get accepted before somebody has died.

With a product like Theriac, public trust was everything.

The first rule imposed on the Theriac making apothecaries, was to display all the ingredients outside their shop for three consecutive days, so everybody could see it was made with the proper ingredients.

Next, the work of pounding and sifting the ingredients, and concocting the final mixture, was also required to happen in a public space.

The whole process usually took a few days, and naturally attracted crowds of spectators.

The apothecaries then made a virtue of necessity, and made it into a publicity show.

Shelves were put up outside the pharmacy to display the ingredients in expensive, decorated porcelain jars.

The workers, seasonal labourers hired for three days each year, dressed in bright colours, with feathers in their hats, ground up the seeds and spices in huge bronze mortars, while they sang more or less lewd work-songs.

Others sat astride long benches, sifting the materials, while managers carried ingredients back and forth between the two teams.

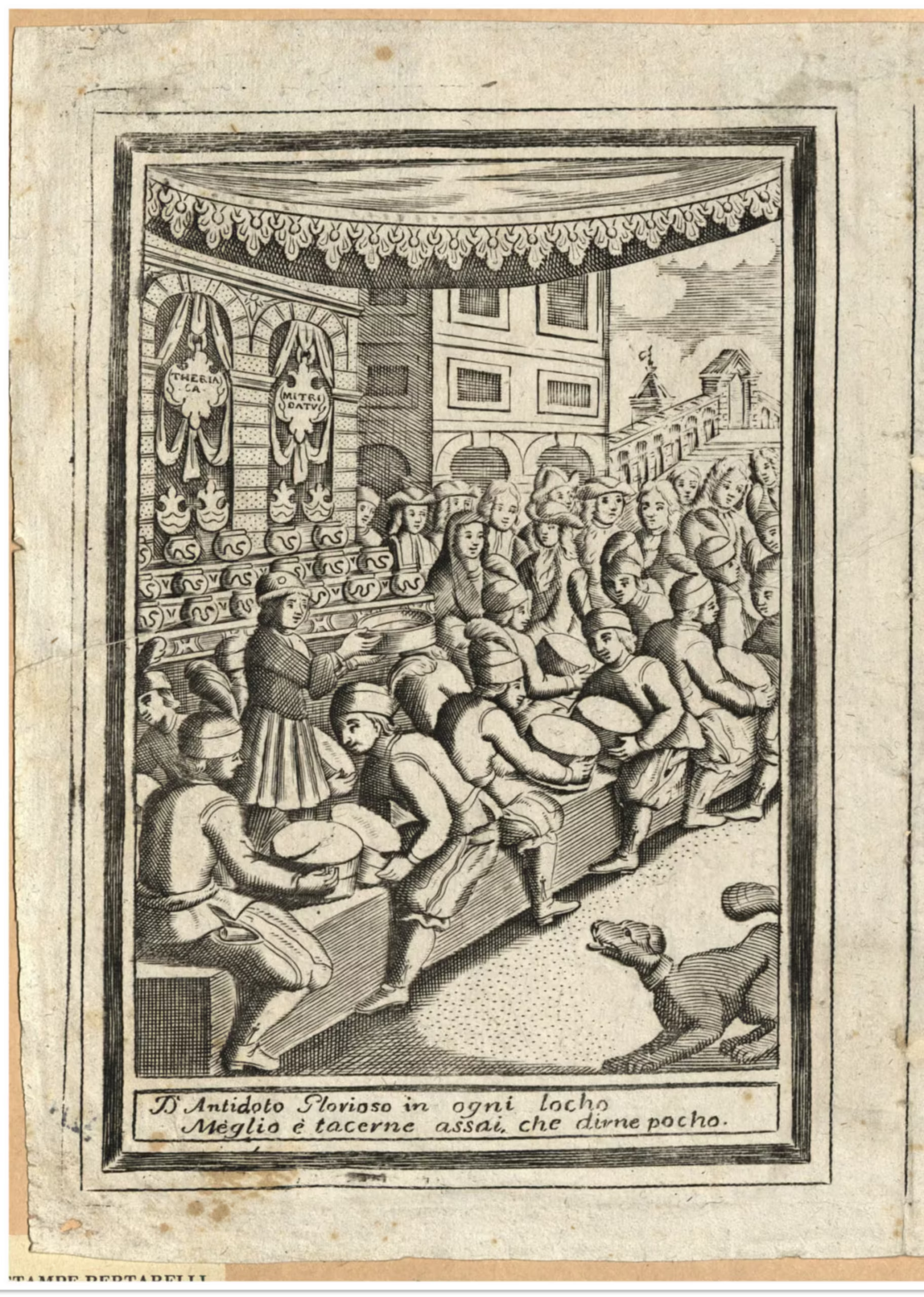

We have some contemporary prints, showing such a setup at the Rialto bridge, for the pharmacy of the Testa d’Oro — the Golden Head.

The pharmacy is long gone, but the shop sign, a large golden man’s head, is still hanging there today, with a faint writing on the wall of “Theriaca Andromachi”.

Go and have a look next time in Venice.

These specific prints also show a baldachin extended across the road for shade, and a bundle of (probably) live vipers hanging on a cord by the tails.

There’s a link to the prints in the show-notes, so click through and see how it was.

Did it work?

The Venetian Theriac brand lasted well into the 1700s, and some pharmacies still produced it in the 1800s.

With the discovery of bacteria and later antibiotics, it disappeared completely.

Still, it was the go-to medicine for numerous conditions for centuries, both in Europe, in the Ottoman Empire and in the Arab world.

Venice made a lot of money on that trade.

So, did it work? Did Theriac actually cure or prevent anything?

There have been several attempts at studying the recipes — they vary quite a bit — to figure out what effect it might have.

Some have even tried to make it, but had to make numerous substitutions, as many medicinal plants have been harvested into oblivion over centuries, and some substances are no longer legal.

Their concoction had a strong smell and taste, which can hardly surprise, given the ingredient list, and they found it gave associations of Christmas. I’d ascribe that last bit to the fact that Christmas is the only time of year we still use some spices, which centuries ago were in common use all year.

For starters, Theriac probably did little harm.

There are only two substances in the recipe, which are toxic to humans: sea onion and opium. However, considering the doses recommended in the ancient recipes, the quantity consumed were well below the level of toxicity in humans.

Overall, most researchers agree that the only ingredient expected to have some effect, is the opium. The quantity is, however, well below the dosage used today for pain relief, so the effect of Theriac on pain will have been limited, but it was there.

Another use of opium is for diarrhoea, and Theriac might have helped there.

In any case, the only probable effect of Theriac would be on the symptoms.

Whether it’s the plague, coughs, quartan fever, dizziness, poor eyesight, or still born fetuses, Theriac would do nothing beyond the placebo effect.

Let’s just conclude, that the promises made in the advertisement from 1688, don’t really stand up to modern scrutiny.

So, was it snake oil? Was it a centuries long fraud at the expense of gullible consumers?

The answer is no.

It wasn’t a fraud because everybody believed it to work, including the apothecaries, who produced it, and the physicians, who prescribed it.

That belief was based on empirical evidence, ancient traditions, religion and plain superstition.

Theriac was, in a way, an expression of the best they could do within the cultural and scientific boundaries of their time.

When those cultural and scientific boundaries started to shift substantially in the 1700s, criticism of traditional remedies like Theriac began to appear, and its use started to decline, to practically disappear in the 1800s.

Theriac as the origin of snake oil

On a side note, the concept of snake oil as a cure-all remedy might have a distant origin in Theriac.

Theriac, being a honey-based electuary, was a sticky, almost fluid substance, and it was largely based on the flesh of vipers.

It was also expensive. Various cheaper alternative remedies therefore circulated in Europe, alongside the real Theriac. They were superficially similar, but made without many of the more exotic and expensive ingredients. Poor peoples’ Theriac, so to say.

Maybe snake oil came out such cheaper alternatives to Theriac, besides the ancient use of snakes, and vipers in particular, in traditional medicines of the time.

What’s still around

In Venice, there are still visible signs of the Theriac industry, even if production ceased a couple of centuries ago.

At the Rialto Bridge, on the side of Campo San Bartolomeo, there’s still the shop sign of the apothecary of the Testa d’Oro on display, along with a faint writing saying “Theriaca Andromachi”.

Testa d’Oro means a golden head, and the sign is a dangling golden head of a man.

The passage is now mostly occupied by the carts of ambulant souvenir vendors, who’ll try to talk to you, if you linger to watch the golden head or read the text.

The two prints, mentioned earlier, depict the Theriac show in this place in the 1600s.

In the Campo Santo Stefano, where the Calle del Spezier enters the square, the apothecary of San Teodoro once was. The modern pharmacy still has the same name, but it has moved to the opposite side of the square, near the church.

The name of the alleyway, Calle del Spezier, literally means Alleyway of the Apothecary. The shop was on the corner, where there is a fashion boutique now.

In the pavement, in front of the shop, there are some circular marks in the paving stones. They are the marks of the large bronze mortars, which were used to ground the ingredients for the Theriac made by the Apothecary of San Teodoro.

That is one of the sites of the Theriac shows in ancient Venice.

Several modern Venetian pharmacies are direct descendants of the ancient triacanti — the speziali authorised by the Republic of Venice to produce Theriac.

The Madonna in Campo San Bartolomeo at the Rialto, the Cedro Imperiale at Campo San Luca (the name means the Imperial Citron), the Orso in Campo Santa Maria Formosa (the Bear), and the Due Colonne in Campo San Canzian (the Two Columns), are all ancient Theriac making apothecaries, which are still operating today, as modern pharmacies.

Their logos, reproduced from the ancient shop signs, often contain the words Teriaca fina in Venezia — Fine Theriac from Venice.

The interior of an entire Theriac making pharmacy from the mid-1700s is on display on the third floor of the museum of Ca’ Rezzonico.

That is the apothecary at the sign Ai Do San Marchi — at the Two St Marks, the sign depicting two winged lions — which was in Campo San Stin.

The Apothecary of the Two St Marks closed in 1908, and the entire interior was donated to the municipality. Some of the vases are from the 1600s, while everything else is from the 1700s.

Finally, Ercole Trionfante (Triumphant Hercules) — a pharmacy which didn’t make Theriac — still has much of the original 1600s interior in the shop.

It is still a pharmacy and wellness shop, and they generally don’t mind if you enter to have a look. It is located at Santa Fosca, where it has been for centuries.

Leave a Reply