The plague doctor, long black cloak, pointy fingers, beaked mask with empty eyes. A giant black raven, the harbinger of a terrible death.

We all know that image. It is part of our culture and mythology. That was how medieval plague doctors looked, right?

Well, guess who didn’t know about the beaked plague doctor? The plague doctors of the 1500s and 1600s didn’t know about the beaked plague doctor.

Yet, they were him. Or were they?

Links

- Episode 17 — Venice and the plague – part 1

- Episode 18 — Venice and the plague – part 2

- Episode 19 — Venice and the plague – part 3

- Episode 20 — Venice and the plague – part 4

Newsletters

History Walks website

Images of the plague doctor

Transcript

The Venetian notary Rocco Benedetti, who wrote an eyewitness account of the 1575 epidemic in Venice — quoted a few episodes back — walked the alleyways of Venice while the plague raged at its worst.

As a notary, his duty was to take down and register last wills and testaments of those who feared death was close. He would stand outside a window with the witnesses, and write down their last wishes. Some of these testaments are still in the Venetian archives.

He was out and about when few others were allowed to.

Benedetti mentions doctors quite often. They were seen as important, they were nominally the authorities in matters of health, but he clearly perceives them as at a loss, impotent in the face of disaster, and as scared as everybody else.

Yet, despite the ample space dedicated to them in his account, he never mentions anybody in a beaked mask.

On the contrary, the doctors died as often as anybody else.

Here, within a few days, fifty-seven of the best doctors similarly died, some having gone in turn, under duress, to identify the dead and sick, others having finally been persuaded by rewards to visit the sick in their homes, or to do service to friends, or to ingratiate themselves with great men. Nor did it help them to go armed with antidotes and preservatives, nor claim to be more wise and cautious than the other.

Some doctors clearly didn’t want to face the patients, and had to be forced to do their job, while others saw an opportunity for economic gain or social advancement in the crisis.

The doctors, who did go to see patients, often died.

Countless charlatans appeared, offering miraculous cures if only Venice paid them handsomely. Most of them failed miserably, and several died trying.

Among the first was Antonio Gualtiero, a Flemish merchant, who, offering to liberate the city in eight days, reminded that the healthy should fast at dawn and drink three sips of their own urine, and before dinner eat a little bread in vinegar with rue, and that the infected should likewise drink theirs, both in the morning and in the evening, putting instead a poultice on the bubo, some of their own warm dung, keeping the wound clean with urine until it was healed.

And while he was in the mood to receive a large provision for this, and to justify the secret he went to the homes of the poor people who had been sequestered to persuade them to do so, one day by bad luck he fell to the ground and bruised his arm, on which a small tumour had developed, and he began to suspect that it was the beginning of a bubo. So to cure it, he put a poultice of dung on it and, constantly drinking as much of the urine as if it were syrup, his blood and vital spirits became so altered that in a few days, vomiting his soul, he ended up killing himself with his remedy, which had been the cause of many people falling ill and dying, as was said.

In this account, a “tumour” means an infected wound, and a “bubo” the swollen lymph nodes, which are tell-tale signs of bubonic plague.

Also:

Then an excellent doctor named Annibale Giroldi came diligently from Ghedi near Brescia, who offered to perform miracles, and he was sent to the Lazaretto Vecchio, as he had requested, with a boat loaded with bottles and stills for distilling and large jars or barrels full of liqueurs, but not as soon as he arrived, he and a servant who had got the bubo, died there within a few days.

There was no cure, and the doctors weren’t even able to protect themselves against the contagion.

The sheer impotence in front of calamity led people, and the state, to fall for such fraudsters.

The real front-line workers weren’t the doctors, but rather the pizzigamorti — the corpse collectors.

They, however, also died in droves, and Venice had to send missives to the cities on the mainland, asking them to send workers for collecting the dead, ferrying the sick to the lazzaretti, and cleaning the houses and the goods therein.

Verona 1630

The next epidemic in Venice, from 1630 to 1631, started in Verona, and it so happens that we also have an eyewitness there, and not just any eyewitness, but an actual doctor.

The plague in Verona started in the spring of 1630, and burned through the city during the summer, to slowly wane in the autumn.

The city had, in January 1630, before the epidemic, some 54,000 inhabitants. One year later, in January 1631, it had 22,000.

Our eyewitness is Francesco Pona, a physician, son of immigrants to the city, and therefore not accepted into the college of the recognised doctors, despite a good education from the University of Padua. He was, however, still allowed to practise for those who wanted his services.

During the epidemic, he wrote a short treatise on remedies, many of which are as scary as the ones mentioned earlier, and immediately afterwards, he published an account of “The Great Contagion of Verona in 1630.”

It is a fascinating read, so bear with me for the long quotes.

For starters, doctors died in droves, just as in Venice two generations earlier. Nothing had changed, and they still didn’t have any treatment or cure for the plague, much less efficient protections against the contagion.

Four Doctors died in a few hours: Francesco Gratioli; Adriano Grandi; and Oratio Gratiani. Grandi in particular, a young man of the highest expectations, a shrewd philosopher, a graceful poet, and a member of the Academia Philharmonica.

And not long afterward, Claudio Giuliari, a doctor of sound practice and one of the oldest members of the College, also died. Just as not long before, other leading Doctors had passed away: Gioan Battista Pozzo, a man of great learning, and among the foremost Doctors of our city; Ottavio Brenzoni, of conspicuous kindness, of very gentle manners, a great physician and a very learned astrologer; and Alessandro Peccana, also gifted with great erudition. Gierolamo Massaroli and Francesco Franco also died.

Note, that these are all highly educated and cultured persons.

They were not itinerant barbers offering odd treatments, or snake-oil peddlers or worse.

These nine men were pillars of civil society in Verona, esteemed both for their medical knowledge and general culture.

Other doctors, for various reasons, retired or stopped working.

Alessandro Lisca, due to his own indisposition, ceased his medical practice, greatly burdened by the death of his wife and children. Giulio Pozzo, a seventy-five-year-old physician, now habitually absent from duties, retired to his estates. Francesco Magno devoted himself to public assistance, albeit without any particular obligation, and perhaps without sharing in the common affliction.

Some got the plague, and survived.

Leonardo Todesco, Canon and Doctor, by helping the poor, assisting relatives, and especially assisting clergy, risked so much for himself that, having contracted the disease, he was in danger of losing his life, but God, perhaps to preserve so rare a jewel for his country and such decor for letters, saved him.

Others, realising that the only strategy for survival, was not to get the plague, practised stringent social distancing:

Only two Doctors regarded themselves with exact circumspection. One was Benedetto Drago, the principal Physician, renowned for his eloquence, learning, and fortune; he rarely left his own home; not so cautious, however, that he didn’t sometimes go near the beds of those wounded by the Plague.

The other was Francesco Pona, who, having decided to scorn gold and to postpone every other human consideration before his own life and family (assuming the clemency of the Magistrate, who with compassion and wisdom, foreseeing and providing, wanted to keep some Doctor out of danger for the country), remained within his own home from mid-June until the end of August, impervious to any attempts that could have moved him from his hardened resolution.

The second one mentioned is the author himself. He names himself in the third person, rather than saying “I”. He was clearly not proud, but he was equally clearly not dead, so he could write what we’re reading.

Pona then continues, now in the first person:

I observe that of the many Physicians who were lost, those most easily exposed to risk were those who were childless. The idea of exposing not only himself by approaching the infected, but of being able to be the transmitter of Death to his dear descendants, extinguishing himself and his own image in his children, appeared formidable for any Man; that therefore married men, and those with more children, with greater disgust and reluctance, showed themselves reticent to care for those, alas, too unfortunate and dangerous.

He then continues excusing himself. He is really not proud.

These two, however, served the public unceasingly by counselling everyone, no matter how ordinary, and even the slightest sick person; hearing each person at a reasonable distance, and providing papers to transport the sick to a place outside the city. Pona also spent a few drops of ink teaching the public how to protect themselves from the plague while there was still time, and then how to treat it in the most dangerous encounters of the disease.

In the deaths of so many doctors, the hopes and lives of a thousand sick people fell, and, in no less sudden and cruel slaughter, the Surgeons fell in greater number. It will serve as a testimony to future generations that pomander and other scented substances (with which each of these was well supplied) are ridiculous armour against so powerful an enemy as the plague.

And now we get to the money quote:

The City of Lucca, following the custom of the French Doctors, in this same evil influence, established that the appointed Doctors should dress in a long cloak, of thin waxed cloth, and that, hooded in the same, with crystals before their eyes, they approached the infected. Thus, the path to contagion is less obvious; because the malignant breath does not have such an easy opening through which it can creep in and be attracted through breathing. I suppose, following this advice, the use of medicinal vinegars; of odoriferous herbs, of proportioned antidotes.

Is this our mythological plague doctor?

We have a cloak, albeit probably not black, as black dyes were rather expensive. There’s a hood, with crystal goggles to see through, but no beak.

Waxed cloth, most likely woollen, as it was most common, was what raincoats of the time were made of. Such a waxed fabric repels water — and in their imaginary — it would also repel the miasma which caused the disease.

This text, written in 1630, published in January 1631, is — as far as I know — the earliest reference of any kind — textual, visual or other — to anything, which might partly resemble the iconic plague doctor figure.

No plague doctor in Venice

What is evident from the accounts of both Rocco Benedetti for the 1575 plague in Venice, and of Francesco Pona for 1630 in Verona, is that there was no figure like the hooded, cloaked, beaked plague doctor anywhere in Venice or its dominions.

The figure of the plague doctor is so striking that it still haunts our imagination. It is unthinkable that such figures would have circulated in Venice and Verona in the 1500s and 1600s, without leaving any trace in these eyewitness accounts.

Our sources would have known.

Benedetti and Pona were both highly educated persons, and very well-connected within wider Venetian society. Had there been something like this hooded and beaked figure around, they would have known.

They were not ignorant or isolated. On the contrary. Both were erudite, intellectuals, published authors, with personal connections way up into the Venetian nobility.

Furthermore, Francesco Pona was a doctor. He should have been inside that suit, and he, and his colleagues, clearly weren’t.

Rather than being protected from the contagion, they died in equal measure to everybody else.

Survivors were either lucky, or they had realised that the only chance of survival lay in stringent social distancing.

Francesco Pona hid in his city house with his entire family for months on end, speaking only to people from an upstairs window.

Rocco Benedetti stood outside the windows, in the alleyways of Venice, while he wrote down the wills of the moribund inside.

The conclusion is straightforward. There was no such plague doctor in Venice during the major epidemics. He wasn’t there.

The 1656 flyers

The earliest images we have of that figure, are not from Venice.

In fact, there won’t be a Venetian image of the hooded, beaked figure until the mid-1700s.

The earliest images are from Rome.

In 1656, a major outbreak of the plague hit Rome and Naples.

A printer produced a flyer with the plague doctor, we all know so well.

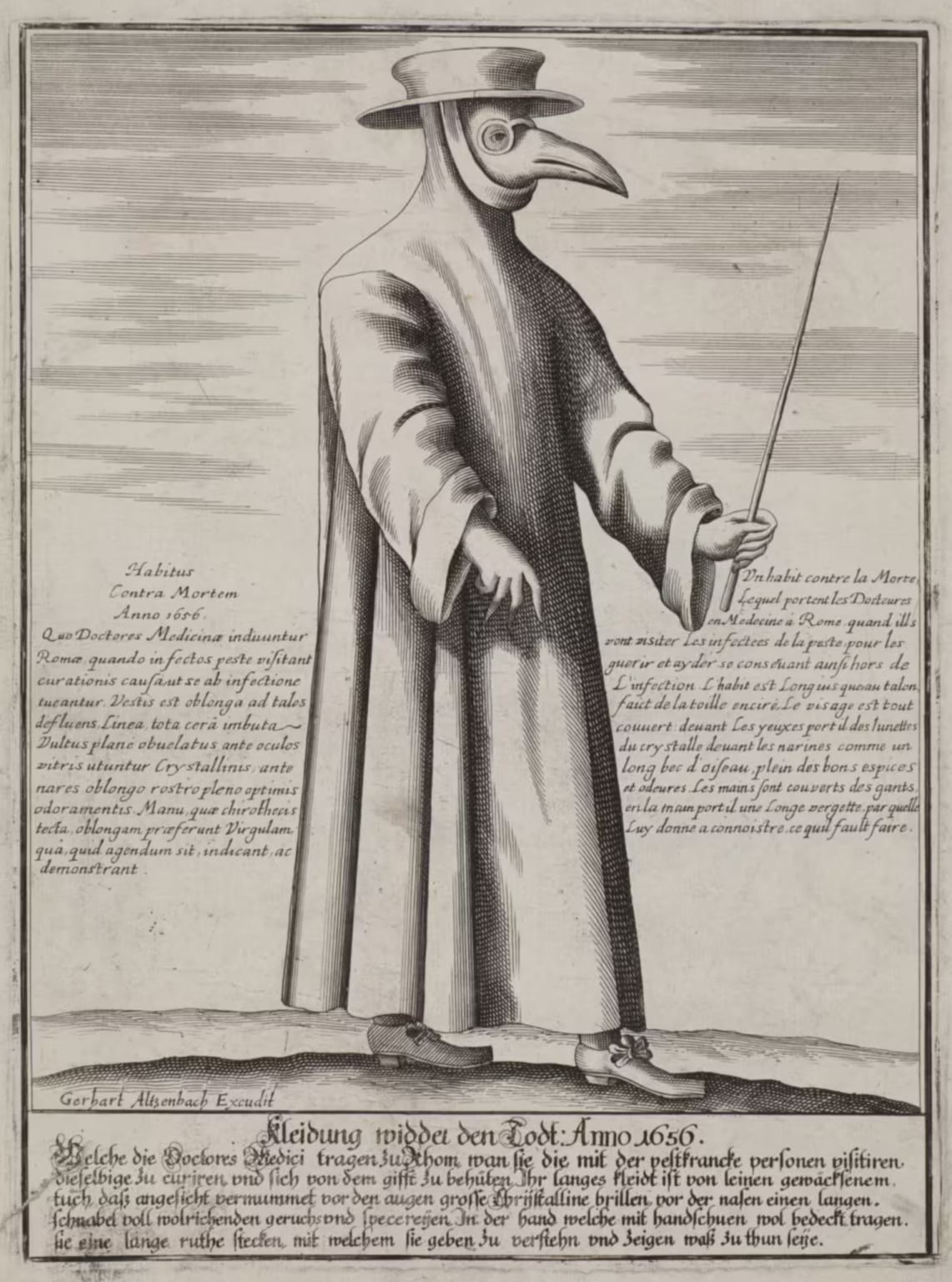

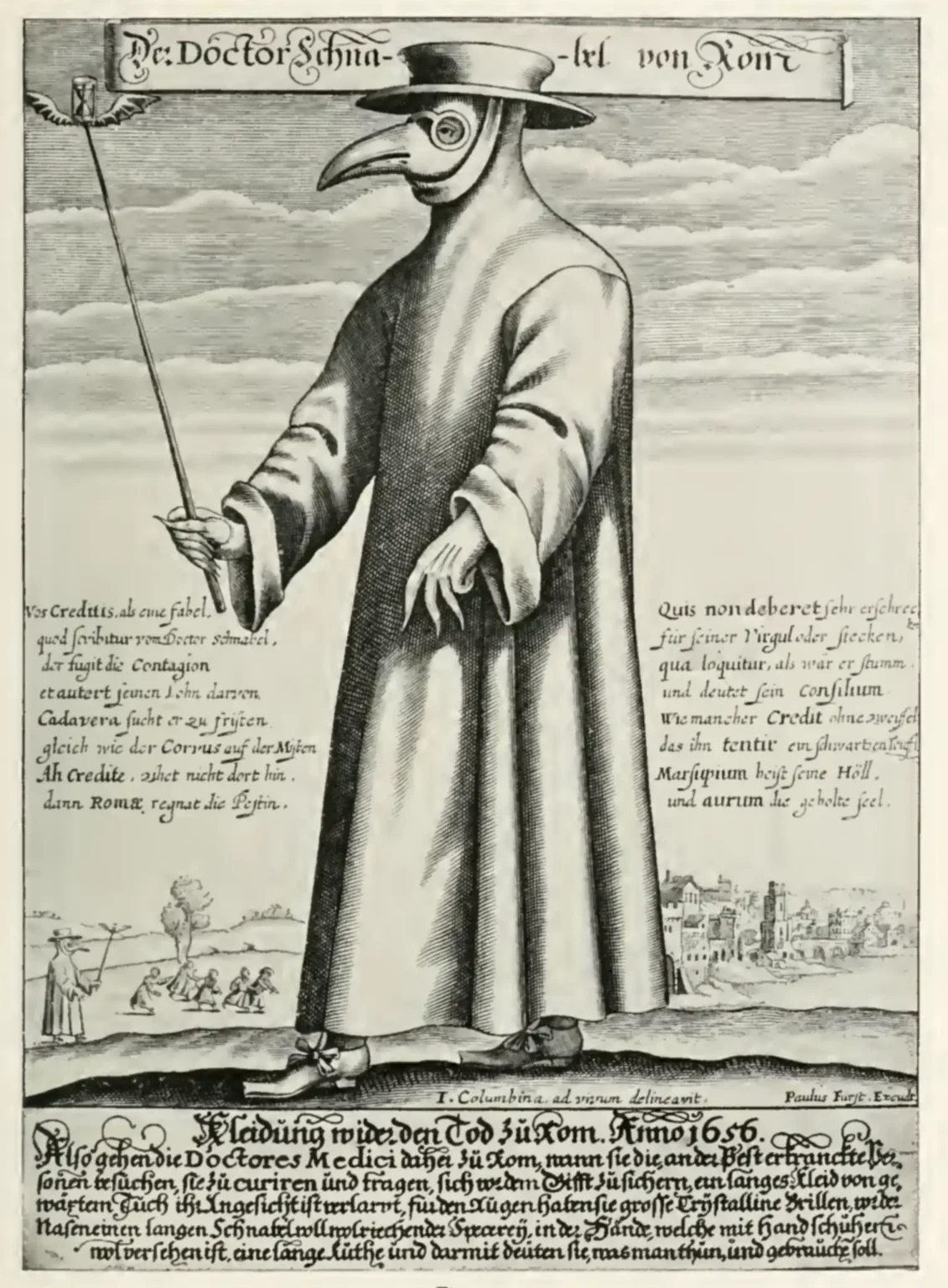

A standing figure, in a cloak all the way to his feet, with long sleeves. His face is covered by a hood and a mask, which has a long crooked beak and glass goggles. He also wears a flat, brimmed hat, and holds a long stick in one hand. He is both human and inhuman, at the same time.

Click through to the Venetian Stories website if you want to see the flyers.

The text on the flyer, in early Italian, says:

The outfit with which the doctors go about Rome to medicate in defence against the bad contagion, is of waxed fabric, the ordinary face, with eyeglasses of crystal, & the nose full of perfumes against the infection. They carry a stick in hand to point, and to demonstrate their operations. In Rome, & in Perugia, For Sebastiano Zecchini, 1656.

This is probably the earliest visual representation we have of the plague doctor figure.

Within the same year, the Roman flyer had made its way to Germany, where another printer — Gerhard Altzenbach — copied it.

The text — translated into German, Latin and French — is mostly the same, except for the added title: “An outfit against Death.”

This flyer was in turn copied by yet another printer — Paulus Fürst — but now both the figure and the text are changed.

It is now very satirical and paints a largely negative image of the plague doctors as greedy and exploitative harbingers of death.

The title — Dr. Beaky from Rome — sets the tone. The figure is more sinister, with pointed fingers and a winged hourglass at the end of the stick.

The winged hourglass is a memento mori — a reminder that we’re all going to die. It literally indicates that time flies and death is near.

In the background, the figure of the plague doctor is shown pursuing a group of youngsters, who’re running away from him.

The text on the sides of the figure — in mixed Latin and German — depicts the doctors as half-studied, greedy frauds who are just after whatever money the sick might have. They will take the money, but offer no relief.

These three pamphlets — and the last more than the others — are the basis for our popular image of the masked, hooded and cloaked plague doctor.

Flyers and truth

What are these flyers, and why were they made?

Such flyers were early modern infotainment. They served both as a visual news source, and as entertainment.

They were printed locally, and sold for small change on the streets.

For the printer, they were a way of making money, as there were far more prospective clients for a single sheet with a catchy image, than for serious books and pamphlets.

This juncture of entertainment, news and commercial interests makes for some issues of truthfulness.

Let’s take an imaginary and slightly extreme example to illustrate the problem.

A printer in the 1600s, in want of cash, has two news items available, but he can print only one of them.

A new pope has been elected, so he can do a “New pope is Catholic! So was the last!” flyer.

Or he can go with: “Three-headed goat born in Egypt under a full moon. Dark times ahead!”

Which of the two will make him more money? I think most of us would say the latter.

Which of the two is more likely to be true?

This is a problem we’re still fighting with, in our information space.

Now, let’s apply that logic to our plague doctor flyers.

If every doctor in Rome went around dressed like that, and had done so for centuries, would the image have any news value?

No, it would be a “Pope is Catholic” story, and it wouldn’t make the printer any money because it would tell a story everybody already knew. Nobody would buy the flyer.

For the flyer to be a profitable proposition, it would have to be newsworthy, out of the ordinary, if not straight up outrageous.

The plague doctor flyer was a profitable proposition.

We know because it made its way all the way to Germany, where others saw the same commercial possibilities, and copied it because they saw a chance of making some money.

Therefore, the plague doctor flyer was far closer to the “Three-headed goat in Egypt” than to the “Pope is Catholic” type of flyer.

Consequently, the logical conclusion is that the cloaked, hooded and beaked plague doctor was not a common sight in Rome in 1656 if he existed there at all.

No smoke without fire

However, if that figure wasn’t a common sight in Rome during the epidemic of 1656, where does the image come from?

It is very unlikely, that the Roman printer pulled it out of thin air.

Remember, Francesco Pona, quoted earlier, did mention something almost, but not entirely unlike the image of the plague doctor.

If there is a truth about the plague doctor figure, where is it?

Pona wasn’t the only writer, who, in the early 1600s, had vaguely heard something about something beaky.

A Florentine, Francesco Rondinelli, wrote about the plague in Florence in the 1630s, and noted:

Each quarter had its own Physician, Surgeon, and Pharmacist, they dressed in waxed fabric, lived separately, …

There’s no mask, or beak, or crystal goggles, but there is some kind of protective suit, that would deflect miasma.

Similarly, in Genoa, Fabritio Ardizzone, a doctor like Francesco Pona, wrote of their experience with the plague of 1656. Regarding physical contact, he wrote:

However, we shouldn’t say that touching lightly communicates the contagion so easily; furthermore a remedy is to wear always over the clothes a cape of leather soaked in vinegar, or of taffeta, or waxed canvas.

Taffeta is a kind of sturdy, and very smooth, silk fabric, which was in common use in the 1600s and 1700s.

Here too, we have the concept of a protective suit, to protect the wearer from exposure to miasma.

We’re still, however, rather far from the iconic plague doctor figure.

Returning to Francesco Pona, he noted in the passing, that the doctors of Lucca, like the French, used a protective suit of waxed canvas.

Like the French.

The French connection

In 1682, the French abbot and aristocrat Michel de Saint-Martin published a biography of Charles De Lorme, who was physician to Louis XIII, King of France in the early 1600s.

This almost hagiographic text contains towards the end this little gem:

He never forgot his goatskin outfit of which he was the inventor, he dressed it from the feet to the head in the form of trousers, with a mask of the same goatskin to which he had attached a half-foot long nose, in order to divert the malignity of the air, we still see the model at Mademoiselle Regnaud, only daughter of the late Monsieur Regnaud, first surgeon to the great Louis the XIII.

This is, in effect, our plague doctor outfit. We might have found him.

In a later edition, Saint-Martin added:

We must take note of the invention of Monsieur de Lorme, who, to be useful to the capital of the Kingdom, and safeguard it from one of the scourges of God, had a goatskin garment made for himself, which the bad air penetrates with great difficulty, he put garlic and rue in his mouth, he put incense in his nose and ears, covered his eyes with spectacles, and in this outfit assisted the sick, and he cured almost as many as he gave remedies. The invention served him eight years later, at the siege of La Rochelle, …

So, with this, we can date the creation of the goat skin suit to the plague in Paris of 1619, as the siege of La Rochelle was in 1627 and 1628.

Connecting the dots

If we now try to connect the dots, we have one doctor, albeit a very prominent one, parading around Paris in such a suit in 1619, and later again at La Rochelle in 1627.

It is not improbable that rumours of such a creation have found its way around medical circles, so Francesco Pona in Verona could have heard something in 1630. He referred to Lucca in Tuscany, but he was aware of a French connection.

The other references to capes and cloaks of waxed canvas could originate from vague news from Paris, but it could just as easily have been the other way around.

If the use of smooth and water-repellent materials were in use earlier, Charles de Lorme might have been inspired by that, but made his suit of a more expensive material, appropriate for his social standing.

It could be either way around.

Likewise, what happened in Rome in 1656, we don’t know.

Maybe some Roman doctor picked up the stories from Paris, and recreated his own suit, which caught the eye of Sebastiano Zecchini, who then made a flyer depicting it, which then popularised the image throughout Europe.

Alternatively, Zecchini might have based his print directly on rumours from France, simply because he thought the Roman doctors ought to dress like that. In that case, the print is much further towards the three-headed goat on the traditional scale from three-headed goat to Catholic pope.

What about Venice

Whatever is the case, it still means that the plague doctor figure has nothing to do with Venice, and yet, today it is perceived as Venetian.

Those masks are all over the souvenir shops in the city.

Besides the beak-less mention of the figure by Francesco Pona in 1631, the first source I have found, which connects the mask with Venice, is from 1710, and then, it doesn’t really.

Lodovico Antonio Muratori was court librarian of the Duke of Modena in the early 1700s. He was a prolific writer, and in 1710 he published a manual on the plague, called “On the management of the plague and how to protect oneself.”

It is a compendium of the state of knowledge of his time, and it was reprinted and translated repeatedly.

Long quote:

It would be good then for all those who leave home, but it will certainly be especially good, indeed necessary for those who have to work with diseased people, to wear an overcoat of waxed cloth, or even goatskin leather, or of other thin leather (these are believed to be best of all) or of Taffeta, or of other Silk fabric because the poisonous spirits of the Disease attach themselves too easily to Woolen garments, but they do not attach themselves except with difficulty (as far as is believed) to the Waxed ones, and to goatskin, and they cannot remain for a long time on unfolded silk. However, note that the silk garments must not be made with luxury, nor with large sleeves and folds, but must be made poor, and rather short; Mercurial having left written that some Venetian Plague Doctors in their days brought upon themselves ruin by having worn long, loose robes and beautiful furs when visiting the Infected, according to the custom of the time. Who doesn’t have Silk, nor anything better, should use at least linen or hemp, rather than wool. Some have sometimes also used to cover the face with a mask, or bautta, on which they placed two crystal eyeglasses; but such scrupulousness is not necessary.

The bauta is a traditional Venetian mask, and it was indeed one of the most common masks in the 1700s, used all year by noblemen and -women alike.

It has a triangular protrusion in front of the mouth, which allows the wearer to drink and eat, without lifting the mask.

Since it is open below, it would offer no protection, and Muratori rightly objects to its usefulness.

Muratori might very well have got the part of the mask wrong. If he had only vague information about the look of the mask, he might have made the association with the Venetian mask, simply because it was the only mask he knew which somehow fitted the unclear description.

I would be surprised, however, if Muratori with his unlimited access to the ducal libraries and archives in Modena, didn’t know about the Roman print from 1656.

In any case, it does leave the presumed connection between the plague mask and Venice rather weak.

There’s another interesting part of this quote, which I don’t want to skip.

The “Mercurial” mentioned, was a prominent professor from Padua, who went to Venice in 1576 to help the Republic of Venice confronting the epidemic. He, and his colleague, argued that the disease wasn’t plague, but after some time, having achieved nothing, they returned to the University of Padua.

If the doctors of 1576 went around dressed normally for their times, the idea that a cape or cloak of some smooth material might protect from the contagion, must have come about in the period between 1577 and 1630.

Grevembroch

Returning to Venice, the first undisputedly Venetian image of the plague doctor figure is a watercolour from around 1750.

Giovanni Grevembroch was a young artist, who worked for a Venetian nobleman, painting and documenting whatever his employer found interesting. He produced several thousand drawings and watercolours over at least two decades.

Over six hundred of these were collected in four volumes on how the Venetians dressed, at the time and in the past.

The plague doctor is included, but from the text associated with the image, it is evident, that Grevembroch has never seen the figure in real life, and that he has painted it on request as a curiosity.

The watercolour is basically a colourised copy of the Roman flyer from 1656. The figure, the pose, everything is the same.

The image, with text and dedication translated, is on the History Walks Venice website, linked from the show notes. Just click through to the website from this episode.

How influential this little painting has been in associating the plague doctor with Venice, is rather unclear. Only one example of the watercolour ever existed, bound in a volume which was kept in the house of a Venetian noble family, where residents and guests could browse them, and have a laugh over the oddities, and the sometimes humorous notes and dedications for each image.

It is, nevertheless, the first Venetian image of the plague doctor, almost a century after the Roman flyer.

The myth

What I take away from Grevembroch’s little watercolour is, that already in the mid-1700s, the plague doctor had become a widespread myth, which people believed to be true, even though they had never seen it.

That myth has been perpetuated ever since, to a point where many just take it for granted that it is so, without asking any questions.

It is a typical example of how an untruth, repeated many times, becomes an accepted reality.

And the figure is really striking. It ignites your imagination. And that is the power of it. It is so striking, that we want it to be real.

Except, in reality, maybe there was only ever one such figure, Charles de Lorme in Paris in 1619. Perhaps there were two, if some unknown Roman doctor picked it up in 1656.

The rest is our imagination getting the better of us.

Leave a Reply