Intro

When playing at war for fun and romance turned into real war, with sieges, baggage trains, warships, winners and losers, who feared for their lives, and white chicken, lots of white chicken.

Illustrations

Links

- Newsletter: The Castle of Love

- Episode 13 — Nobles and Citizens

- Episode 5 — Ascendancy

- Episode 6 — Wealth, power and empire

Transcript

The year was 1214, or maybe 1215, or even 1213. There’s a bit of uncertainty there, as our sources don’t agree.

Anyway, the good people of the March of Treviso decided to have a grand party.

Now, this is the high Middle Ages, so imagine a medieval festival, with loud trumpeters and flying banners, armoured knights jousting, ladies in pointed hats and expensive dresses of silk and brocade, grand balls in the evenings, and endless dinners.

Just as our sources don’t all agree on the date of the event, neither do they on the reason for the festivities.

However, whatever the reason, invitations went out to neighbouring cities far and wide, including Padua, Verona and cities in Lombardy.

Noblemen and women came to Treviso in their thousands, for a week of fun, jousting, games and parties. Everybody were dressed in their finest because this was a chance to show off for the entire region.

In the 1200s, all these cities were still more or less small independent states, so it was an international event.

It is not entirely clear if the invitation also went to Venice.

The reason for this uncertainty, besides maybe an anti-Venetian bias in some of our sources, was that Venice was not a part of the same world as the mainland. The mainland had, since the time of the Lombards, been part of the Kingdom of Italy, which again was part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Venice, on the other hand, was born Byzantine and had remained eastern.

This divide went back to the 600s and 700s with the Lombard invasions, and it was cemented with the war between Venice and the Franks in 809, which entrenched Venice firmly in the Byzantine world.

So, all the semi-independent city states, duchies and marches on the mainland belonged together under the umbrella of the Holy Roman Empire, of which Venice had never been a part.

However, whether invited or not, the Venetians showed up for the party.

A Castle of Love

The plan in Treviso was for a week of games and entertainment, feasts and balls, for nobles and wealthy citizens alike.

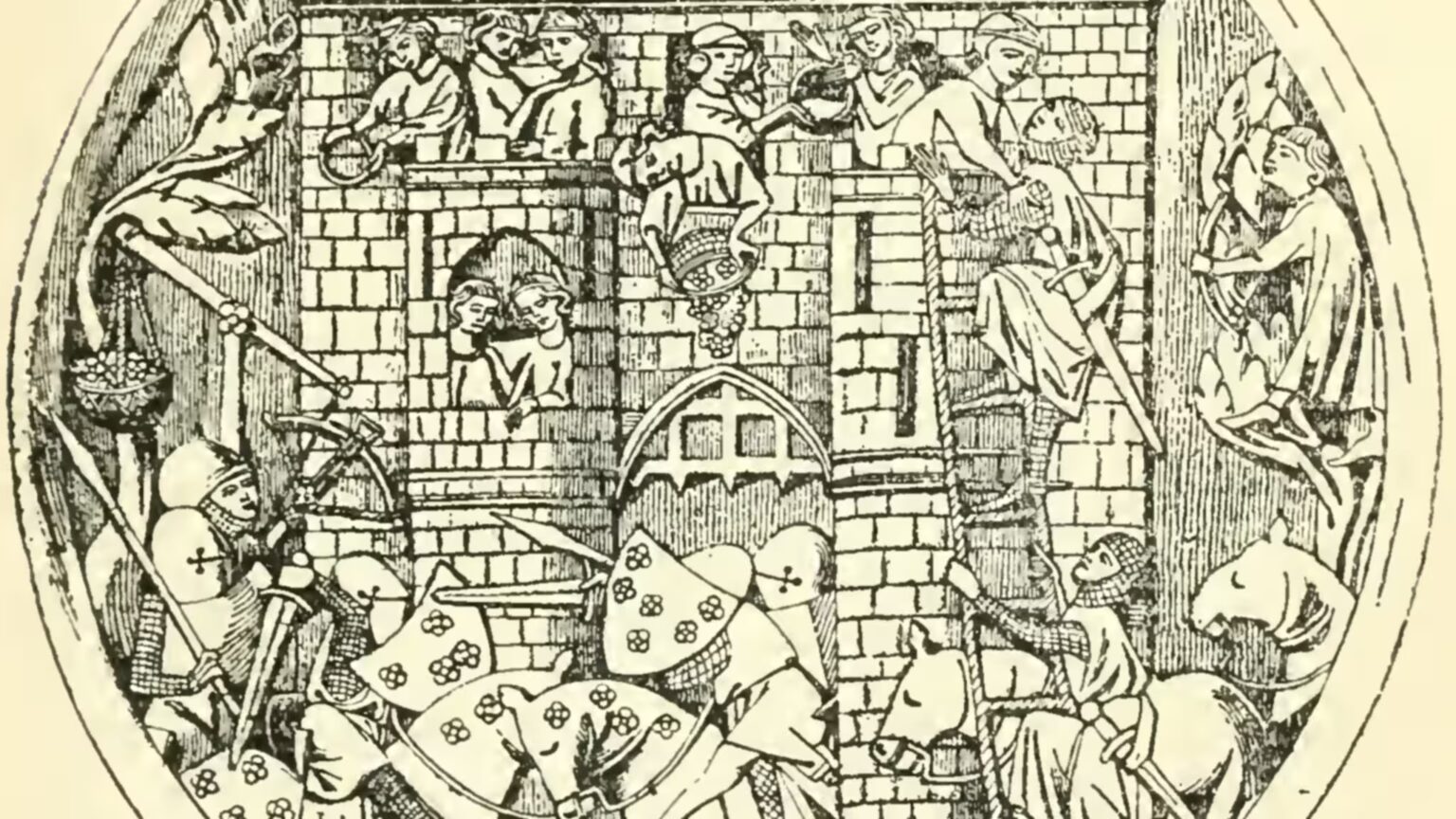

One of the games planned was a Castle of Love.

The game of Castle of Love is well-known from later romantic troubadour literature, but it must have been around for a while, as this event is about a century earlier than most literary references.

A Castle of Love was a temporary wooden castle, built for the occasion. It was a small castle, but natural size, so several storeys tall, with a front gate, surmounted by battlements and flanked by towers.

Different groups of noblemen, all dressed for war, besieged the castle, trying to take it by storm, breaking the gate or scaling ladders to the battlements, or by playing music and singing romantic serenades to convince the defenders to surrender.

The defenders of the Castle of Love were the noblewomen, assisted by their ladies in waiting and maids.

The arms used in such battles, were an assortment of fruits, flowers, spices, perfumes and musical instruments.

Here is a contemporary description of the event, by Rolandino of Padova, who is one of our main sources:

In the year 1214 Albizzo da Fiore was Podesta of Padua, a prudent and discreet man, courteous, gentle, and kindly ; who, though in his government he was wise, lordly, and astute, yet loved mirth and solace.

In the days of his office they ordained at Treviso a Court of Solace and Mirth, whereunto many of Padua were called, both knights and footmen. Moreover, some dozen of the noblest and fairest ladies, and the fittest for such mirth that could be found in Padua, went by invitation to grace that Court.

Now the Court, or festivity, was thus ordered. A fantastic castle was built and garrisoned with dames and damsels and their waiting-women, who without help of man defended it with all possible prudence.

Now this castle was fortified on all sides with skins of vair and sable, sendals, purple cloths, samites, precious tissues, scarlet, brocade of Bagdad, and ermine. What shall I say of the golden coronets studded with chrysolites and jacinths, topaz and emeralds, pearls and pointed headgear, and all manner of adornments wherewith the ladies defended their heads from the assaults of the beleaguerers ?

For the castle itself must be assaulted ; and the arms and engines wherewith men fought against it were apples and dates and muscat-nuts, tarts and pears and quinces, roses and lilies and violets, and vases of balsam or ambergris or rosewater, amber, camphor, cardamums, cinnamon, cloves, pomegranates, and all manner of flowers or spices that are fragrant to smell or fair to see.

The game of Castle of Love is courtship disguised as military conquest, where the men must prove their valour and the women defend their virtue.

I guess that’s why it would have been detrimental to the fun to simply use the traditional siege tactics of simply starving the women out.

The apparent narrative of the game — between the participating men and women — is one of amorous conquest.

There’s another narrative, targeted at the non-participants.

The objects used in the fight, and worn by the participants, were all very expensive. The game of Castle of Love was also an incredible display of wealth and opulence.

Rolandino talked of “skins of vair and sable” and of “ermine”. In medieval siege warfare, wooden structures on both sides were often covered in wet animal hides, to prevent the enemy from setting them on fire. Here, however, they used vair, sable and ermine, which are some of the most expensive types of fur.

The “purple cloths” and “scarlet” are rare and expensive dyes, used for various types of cloth. Purple, especially Tyrian Purple, was the most exclusive and rare dye in antiquity, used by Roman senators on their togas, later in the dress of Roman and Byzantine imperial dynasties, which is why it is also called Royal Purple or Imperial Purple.

In Constantinople, Porphyrogénnētos — literally “born in the purple” — meant a prince born to a ruling emperor, who wore purple. The imperial palace in Constantinople even had a special room, all clad in porphyry, a rare rock with the same colour, where empresses gave birth, so theirs son could literally be “born in the purple”.

Returning to Rolandino, he mentioned “sendals”, “samites”, “precious tissues”, and “brocade of Bagdad”. These are all various types of silk fabrics, while “chrysolites and jacinths, topaz and emeralds, pearls”, are all precious stones.

Finally, ambergris is a substance extracted from the stomach of whales, which has a particular fragrance. It has been used in perfumes for centuries.

The Castle of Love was essentially a massive food fight using the equivalent of caviar, truffles and foie gras, wasting precious items, just to show that you could afford it.

The enemy arrives …

Rolandino of Padova, who wasn’t a friend of Venice, continued:

Moreover, many men came from Venice to this festival, and many ladies to pay honour to that Court ; and these Venetians, bearing the fair banner of St. Mark, fought with much skill and delight.

Yet much evil may spring sometimes from good beginnings ; for, while the Venetians strove in sport with the Paduans, contending who should first press into the castle gate, then discord arose on either side ; and (would that it had never been !) a certain unwise Venetian who bare the banner of St. Mark made an assault upon the Paduans with fierce and wrathful mien ; which when the Paduans saw, some of them waxed wroth in turn and laid violent hands on that banner, wherefrom they tore a certain portion ; which again provoked the Venetians to sore wrath and indignation.

The rivalry between Venice and Padua was ancient.

Each city was the capital of an independent duchy, but Padua was much older than Venice. It already existed in Roman times, while Venice was the up-start. In fact, one of the later legends of the foundation of Venice, places the start of Venice at the hands of tribunes — Roman era city officials — from Padua.

Venice, however, was very much on the ascendancy at this time. The close association with the Byzantine Empire had allowed Venice to grow incredibly rich on trade with Constantinople and the wider Levant, which was exacerbated by the recent conquest of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade.

This conquest and sack of the Byzantine imperial capital was just ten years before the feast in Treviso, and Venice was still reaping the spoils of that endeavour.

For the Paduans, the Venetians were the nouveau riche who didn’t miss a chance to flaunt their recently acquired wealth.

For the Venetians, the Paduans were the stuffy old have-been, who stuck their nose up at the Venetians, but who were clearly on the decline.

Rolandino, who was from Padua, put the blame squarely on the Venetians. The Venetian sources likewise unambiguously blame the Paduans.

A short note on the flag.

The banner of St Mark used here was not the gold and red gonfalone with the winged lion. That flag came centuries later. Venice didn’t really have a flag in the 1200s, but the navy used a flag with the figure of St Mark standing, sometimes on a blue background.

We know this because Genoa used a similar flag with the figure of St George, which caused confusion when the navies of Venice and Genoa clashed. Their two flags were too alike to distinguish in the heat of battle.

Then, who knows, maybe bringing a flag associated with the Venetian navy, shortly after that same navy had conquered the Roman Empire, was bound to be seen as a provocation, as a statement of supremacy over the others.

Let’s return to the account of Rolandino da Padova:

So the Court or pastime was forthwith broken up at the bidding of the other stewards of the court and of the lord Paolo da Sermedaula, a discreet Paduan citizen of great renown who was then King of the Knights of that court, and to whom with the other stewards it had been granted, for honour’s sake, that they should have governance and judgment over ladies and knights and the whole Court.

Of this festival therefore we might say in the words of the poet, ” The sport begat wild strife and wrath ; wrath begat fierce enmities and fatal war.”

For in process of time the enmity between Paduans and Venetians waxed so sore that all commerce of trade was forbidden on either side, and the confines were guarded lest anything should be brought from one land to the other : then men practised robberies and violence, so that discord grew afresh, and wars, and deadly enmity.

So, the festival was broken up after the unauthorised skirmish between the Paduans and the Venetians, and everybody went back home with their grievances intact, if not increased.

It’s time for another aside because there are some interesting words in here to unpack.

The people of Treviso held a “court” — like the court of a king.

And, in fact, they had a “king”.

The person in charge was King of the Knights. He set, enforced and adjudicated the rules, that is, he had legislative, executive and judicial powers within the realm of the games, just like a real medieval king.

Who was this “king”? He was, in Rolandino’s words, a “discreet Paduan citizen of great renown”.

So he was a highly respected individual, but also a “citizen”. He was not a nobleman, and yet he was chosen as “king” of the “court”.

This should ring a bell for those who listened to the previous episode 13 on nobles and citizens in Venice. In situations of fierce competition between different parts of the nobility, they needed an outside arbiter, but also somebody respected and trusted, so they picked an esteemed citizen.

The entire structure and organisation of the games was copied from the wider society in which they all lived.

Make war, not love …

The “king” broke up the “court” because the “knights” had played foul.

The fight which had broken out in Treviso was, however, much more a symptom, than a cause. The tension, which had turned to open conflict at the Castle of Love, didn’t originate there, and it didn’t go away afterwards.

There were some far more substantial issues between Venice and Padua.

The two neighbouring duchies of Venice and Padua both relied on resources, over which the other exerted influence.

In short, both were capable of causing noticeable harm to the other.

The main point of contention was the use of, and hence control over, the river Bacchiglione which passes through Vicenza, then Padua and finally exits a bit south of Chioggia.

The Venetians needed the river to send their goods inland, but it passed through the territory of Padua.

Padua needed the river for access to the sea, but it flowed through the territory of Venice in the area of Chioggia, to the south of the current Venetian lagoon.

The Venetians had built a fortification on the river — the Torre delle Bebbe — not far from Chioggia. The existence of this fortified tower was a very concrete expression of the desire of Venice to control traffic on the river.

Like so many of the wars the Republic of Venice fought, this too was much more about trade and money, rather than about honour and a torn flag.

Following the “battle” at the Castle of Love, both sides blocked traffic on the river, in the hope that it would hurt the other side more.

In the autumn of 1215, Padua in alliance with Treviso sent troops down the Bacchiglione to the Torre delle Bebbe to open the passage by force, and remove Venetian control over the estuary.

The Venetian garrison in the tower dug ditches and created earth mounds around the tower, and filled the lower part of the tower with sand, to strengthen it against a besieger.

The forces from Padua attacked the tower, but were rebuffed.

As the fighting around the tower on the shore of the river continued, the troops from Treviso were approaching, to help the forces from Padua.

However, before Padua and Treviso could join forces, the tide came up much higher than normally, entered the river estuary, and flooded many of the fields around the tower.

The Paduans had to quickly retreat to higher grounds, and the Trevisan forces were prevented from joining them.

Then, a small Venetian navy of rowed war galleys came up the river, crossed the flooded fields and attacked the forces of Padua on their impromptu camp on the higher ground.

It was a complete rout.

Many Paduan men drowned as they tried to flee the area, and hundreds were taken prisoners by the Venetians, including several hundred noblemen from Padua.

The troops from Treviso left, and returned home.

Between three and four hundred prisoners — half of them noblemen from Padua — were brought to Venice in triumph.

Chicken peace …

It was common in Medieval warfare to dispose of the poor prisoners in some, preferably profitable, way, while keeping the wealthy or important prisoners for ransom.

In short, to cash in on the advantage.

Poor prisoners could be sold into slavery, or used as forced labour. In the case of Venice this was usually in the navy. The prisoners became rowers on the Venetian war galleys, chained to the benches of the vessel for the rest of their probably short life. Alternatively, if no profit could be derived from them, they were simply killed.

People of means, who were taken prisoner, would often be held for ransom.

About a century later, in the early 1300s, Marco Polo dictated the story of his journeys in China to a co-prisoner from Pisa, in a dungeon in Genoa. Polo, a wealthy Venetian merchant, had finished there after a lost naval battle between Venice and Pisa on one side, and Genoa on the other. Marco Polo and his companion from Pisa were later freed, and Marco Polo returned to Venice.

However, if other concerns overcame the monetary interests, even important or wealthy prisoners might simply be executed, if that served the interests of the victor the better.

Almost two centuries after the War of the Castle of Love, at the very end of the 1300s, Venice had imprisoned all the male members of the ducal family of Padua. After a debate about what to do with them, it was decided to eliminate them, and they were unceremoniously strangled in their prison cells. Shortly after, Venice put an end to the Duchy of Padua, and reduced it to a “subject city”.

Returning to our War of the Castle of Love in 1215, the many captured Paduan noblemen no doubt feared for their life. Having taken up arms against Venice would hardly go unpunished.

The prisoners were taken to Venice, and paraded through the city for everybody to see.

What then for the prisoners?

Venice had a choice to make, which would, however, influence the future relationship with the next door duchy. They could let them go, but then Padua might feel emboldened, and attack again when they saw the chance.

Alternatively, they could have them all put to death, in which case there would probably be a blood feud with Padua for generations to come. If, in a future fight, Venetian nobles ended up prisoners in Padua, their fate would be sealed.

Finally, Venice could use the occasion to extract money and wealth from Padua, to a larger or smaller extent.

After some deliberation, the doge, Pietro Ziani, decided that leniency was the better strategy.

He would let all the prisoners go home, safe and sound, on one condition: First Padua would have to deliver to Venice, two white chickens for each prisoner.

Venice required Padua to pay up in live birds, but slightly unusual birds. Most chicken aren’t white.

Probably, Padua would have preferred paying in cash from the treasury.

Now they had to collect between 600 and 800 white hens from across the duchy, and transport them in cages to Venice.

It would be a slow, noisy and highly visible affair.

They would have to scour the entire territory of the Duchy of Padua, going from farm to farm, from house to house, to find and collect the birds.

Absolutely everybody in the entire duchy would know what was going on, from the highest to the lowest. There was no hiding such an operation.

So, maybe, rather than leniency, the Venetian strategy was one of humiliation — an attempt at undermining the authority and legitimacy of the ruling elite in Padua.

Precedents

When the hundreds of chickens arrived in Venice, they were distributed to the lower classes during a grand victory celebration in the city.

The people naturally clamoured for the tribute to be imposed annually because what’s not to like about a party with free food, especially if you’re poor and rarely have any kind of meat in your diet.

The doge, however, refused to impose the tribute annually, most likely because Venice wasn’t in a position to impose it, once the prisoners were allowed to go home.

The request of the Venetian lower classes appeared because there was a precedent, and even a fairly recent one at that.

Due to the invasions of the Lombards in the 600s, the Patriarch of Aquileia had fled to the lagoon city of Grado in 717. The Lombards, who were also Christians, albeit Arians, placed on of their own on the throne of the patriarch.

Consequently, there were two patriarchs, both claiming jurisdiction over the same territories: one in Aquileia which became part of the Kingdom of Italy under the Holy Roman Empire, and another in Grado, which was in the Venetian dogado.

The conflict was never resolved, and regularly resulted in armed fights between the two patriarchs.

In 1164, the Patriarch of Aquileia attacked the Venetian Patriarch of Grado.

What better way can there be to turn the other cheek than an armed attack on your neighbour? That’ll teach them humility.

The Venetians, however, came to the aid of “their” patriarch, and defeated the forces from Aquileia. They also captured the Patriarch of Aquileia himself, who, humbly, had led his troops in battle.

As punishment, he was paraded through Venice to the cheers of the crowds, and the republic imposed on the Patriarchy of Aquileia a tribute of twelve pigs and a bull to be sent to Venice for the carnival, each year, in perpetuity.

This tribute was delivered annually until 1797.

The animals were slaughtered, and the meat consumed during the carnival festivities, which was, needless to say, hugely popular with the crowds.

The poorer Venetians probably wouldn’t have said no to another such annual feast, with plenty of free food, after the war with Padua.

But, alas, no free food every year after the War of the Castle of Love.

Leave a Reply